Corn-Revere: Broadcasting Deserves Full 1st Amendment Protection, And Social Media Should Keep Theirs

Since leaving FCC as a legal assistant to the late FCC Commissioner James Quello in 1994, Robert Corn-Revere has been busy, establishing himself as a leading First Amendment attorney, representing not only broadcasters in their never-ending battle over indecency at the FCC, but also other media companies and individuals who feel their free speech rights have been infringed upon.

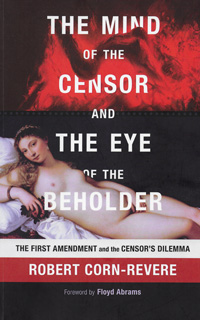

Much of what he has learned over the years has been distilled in his new book, The Mind of the Censor and The Eye of the Beholder, a brisk, but substantive history of government censorship stretching back to nearly to the Civil War.

Much of what he has learned over the years has been distilled in his new book, The Mind of the Censor and The Eye of the Beholder, a brisk, but substantive history of government censorship stretching back to nearly to the Civil War.

It’s not a lawyerly tome. The history is built on tales of America’s flesh-and-blood censors – Anthony Comstock (books and other printed matter); Frederic Wertham (comic books) Tipper Gore and James Baker’s wife Susan (recorded music); and Newton “Vast Wasteland” Minow and Brent Bozell (broadcasting).

In this interview with TVNewsCheck Editor at Large Harry A. Jessell, Corn-Revere explains the courts’ reluctance to extend full First Amendment protection to broadcasters and allow the FCC to continue to meddle in broadcast programming.

He provides some free legal advice to broadcasters who might be understandably confused by the state or indecency regulation and says that with the right case, broadcasters might finally free not only from content regulations, but ownership restrictions as well.

And he says that, despite all the new alarms and concerns they raise, Facebook, Twitter and other social media deserve no less protection from government censors and regulators than any of their predecessors.

An edited transcript.

As your book details, we have had a series of federal court decisions over the years that slap down FCC indecency enforcements efforts, but never quite get to declaring them unconstitutional and freeing broadcasters from indecency constraints. How come?

The court has always been reluctant to get into this. It came up right after radio regulation began in the twenties and early thirties where the question was potentially going to go to the Supreme Court. At the time, Chief Justice William Howard Taft said he wanted to put off for as long as possible resolving the constitutional status of broadcasting because to him this mystery of radio was akin to the occult and so he just didn’t want to deal with it.

And I thought we had such a case in the latest round of indecency cases that went to the Supreme Court in 2012, cases involving the Super Bowl wardrobe malfunction and the case involving the music award shows on Fox where the FCC and Congress had been toughening the indecency policy and the constitutional issue was teed up by the Second Circuit to have the Supreme Court decide it.

During the oral arguments on that case, I think it was Justice [Samuel] Alito who said why do we have to deal with this, why don’t we just wait until broadcasting disappears. So, the court has been really reluctant to deal with these issues and particularly the constitutional status of broadcasting because it is a constitutional anomaly.

You have a First Amendment that was adopted saying that Congress shall make no law restricting the freedom of the press or speech. It was adopted in part reaction to European press licensing. But, of course, once we had a new technology emerge in the early twentieth century, Congress’s reaction was to license it to establish the very kind of press licensing that prompted the adoption of the First Amendment in the initial stages.

You would think that, if you simply acknowledge that traditional First Amendment standards apply, you would put an end to all of that back and forth.

So, given the current uncertain state of the law, give broadcasters a list of dos and don’ts for avoiding FCC trouble on indecency.

I can give you a list of risk factors.

Give me three.

As broadcast regulations are currently constituted, the indecency rules do not apply after 10 p.m. But I think most broadcasters would recognize that it is going to be a risk to broadcast something that will be likely to draw complaints and then the FCC will have to deal with it.

The FCC ultimately is a political body, and they will respond to political demands both from the public and from Congress. Whether or not the FCC would prevail in a case of showing nudity after 10 p.m., you could likely end up having to defend a case for that.

The second risk factor would be anything involving profanity. The standards have changed over time, but the seven George Carlin words would be examples of the kinds of things that if you used them in a prime time broadcast it would be risky and it could lead to a complaint and lead to a case.

The third risk factor would live broadcasts because live spontaneous broadcasts are situations in which pretty much anything can happen and as we know from the Super Bowl broadcast, the FCC can attempt to hold broadcasters responsible for things that happen in those live broadcasts.

As you point out in the book, the FCC doesn’t have to go through the trouble of fining a station and then defending the fine in court. It can just blackmail the station as it did in the case of WDBJ in Roanoke, Va. [Editor’s note: In 2015, the station inadvertently aired a tiny pornographic image for a second or two that appeared on a computer screen in the background of a newsroom shot. A producer was working on a story about a public employee who was in trouble for working in porn. Upon a complaint, the FCC fined the station $325,000 and, because the station was in the process of being sold, it threatened to withhold its approval of the sale if the station challenged the fine and didn’t pay up.]

Blackmail is such an ugly word.

Well, that’s what you called it in your book.

Yes, I did.

Now this happened after the latest round of Supreme Court decisions that drew some constitutional lines on how far the FCC could go. I believe it was perceived pretty accurately by the commission that if they had to defend their standard in court again, they would have difficulty doing it.

They were able to dispose of this case and not have to decide the constitutional merits. Now there have been cases in the past where the agency has allowed a transaction to go through, but also allowed the former owner of the station to preserve its challenge to the finding, but in this case it refused to do that.

That doesn’t seem right.

No, it doesn’t. You are depriving someone of their day in court.

Frankly, indecency is not the principal regulatory concern of TV broadcasters these days. They are looking for relief from ownership restrictions. Is there a case that can be made to knock them out, perhaps on First Amendment grounds?

Well, there could be and, again, you would be looking for the right set of facts. One of the things about broadcast regulation is that it has always been tied in one way or another to the technology.

The original justifications were that because of the nature of the electromagnetic spectrum that Congress had to regulate broadcasting in a way that was fundamentally different from other media.

Now I take issue with that, but that was the justification that was used, and it was accepted by the courts and in the sixties and seventies was probably the high point for the courts accepting the FCC’s justifications for various kinds of regulations, the structural regulations included.

I think that as technology has changed and as broadcasting has been joined with a raft of competition from all sides, the arguments for regulating broadcasting differently become less compelling. You could make a constitutional argument and it would depend on having the right case and the right set of facts.

Broadcast indecency is kind of old news. The great First Amendment debate today is over what to do about social media. They are the focus of great concern by the public and by policymakers as printed matter, recorded music, comic books and broadcasting were in their heydays.

Now the kneejerk response by a lot of people is, we need a federal social media commission, we need some kind of regulatory solution and, having worked in government and having seen how these types of things operate, my feeling is that that is a problem.

There is not a problem that can’t be made worse through government intervention and the regulatory solution is almost always going to be worse than the disease. I mean pick your poison. Is the problem that these big social media corporations have too much power? What happens when you put the government as a layer over those social media corporations and it is making the decisions?

Now you have just consolidated the effective power in one source. You can decide for yourself whether or not that would be a good thing based on who you put in charge and that is going to change from administration to administration. So, trying to find a silver bullet solution to a very complicated problem presents bigger difficulties and bigger problems.

What we should do about it really comes down to whether or not people deserve to be free. Most of the problems people identify with social media come from what people post on it, what people say to each other. If you don’t like that then you don’t like the concept of freedom.

Now, can there be problems to dealing with that? Of course there can, and there are a lot of things that get posted that create problems. We have got to find a way to deal with that, but I think the solution really is to find a way to allow people to have a better understanding of government, have a better understanding of history, understand how to critically evaluate information, have media literacy.

What about Donald Trump’s idea? Use the leverage that you can get from Section 230 to restrain social media companies from curating what is posted on their sites so that they become public squares where everybody can say what they want. That sounds like freedom to me.

Well, it is not real freedom for the platform owners. You are ignoring the idea of a platform owner having the ability to decide what kind of community they want to foster, what kind of rules they want to have. I think that is a First Amendment right as well. Platform owners ought to have that right. And most users are pleased that platform owners try and have some types of terms of service or moderation rules.

The difficulty that comes in is that people disagree on what those rules ought to be. To use Trump as an example, he disagrees with the way Twitter or Facebook treated him. Oddly enough, he is creating his own social media platform that includes terms of service, as I have read about them, that say this is a free speech platform except you can’t criticize me or the platform. Therein lies the problem.

Everyone wants free speech, but they want to be able to limit what the other guy says, which is ultimately the flaw in putting one entity, putting the government in charge of deciding what the rules should be for everybody.

Comments (0)