100 Days Under Fire: The Inside Story of How Cable News Has Covered Pandemic and Protest From the Frontline

A protestor stands outside a burning building in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Chandan Khanna/Getty Images

This is a special preview of Mediaite+ — our new premium subscription offering. For more in-depth, insider stories, plus an ad-free viewing experience, subscribe today.

The events of the past 100 days have presented a challenge unlike any the cable news business has ever seen. The coronavirus pandemic resulted in the headquarters of all three major networks being largely shut down — requiring home studios to be set up on the fly, and broadcast operations to be completely overhauled. And just when the industry appeared to be settling into a new normal, protests against police brutality erupted nationwide — forcing correspondents and their crews to face down dangerous situations to stay on the air at a time when their viewers need them most.

There have been countless obstacles to cable news broadcasting presented by pandemic and protest. The challenge of the last 100 days has required ingenuity from control room staffs, tenacity from field reporters, and bravery from production teams.

Over the past several weeks, Mediaite has spoken with dozens of correspondents, anchors, and behind-the-scenes personnel from the three major cable news networks to find out how they’ve navigated this unprecedented time. The end result is this story — one of the most comprehensive we’ve ever published.

• • •

Part I: Rage in the Streets

It was just prior to 8 p.m. local time, Sunday May 31. The sun was setting over Minneapolis — the pending darkness bringing a close to one of the most calamitous weekends in recent American history.

CNN correspondent Sara Sidner had been there for it all. Every night for the past four, Sidner and her team found themselves right in the middle of the action — standing directly between a giant mass of furious protesters, and an army of police officers on edge.

“There was — for lack of a better word — rage in the streets,” Sidner said of the fraught scenes she encountered.

Rage in the streets of Minneapolis. Rage in the streets of America.

Indeed, it was in the Twin Cities where the rage fomented. This, after all, was the place in which George Floyd was killed in police custody. The shocking eight minute 46 second video showing officer Derek Chauvin’s knee pressed against Floyd’s neck set off a furor. Protests erupted across the country. Many peaceful, many not.

Sidner and her team witnessed demonstrations which fell squarely in the latter category. Police shot rubber bullets and used teargas against protesters who, in turn, threw water bottles, rocks, and whatever else they could find. The CNN correspondent had seen a police precinct burned down, colleagues arrested, and utter chaos all around her.

She worked 16 hour days, and slept for just a few hours per night. But despite the taxing schedule and the lack of rest, the adrenaline kept her going. The adrenaline, and the gravity of the work she was doing.

“The importance of the story, and the voice of the people that you need to get out there, far outweighs any sleep that you may need,” Sidner said.

And on that Sunday night, the voice that the CNN correspondent got out there belonged to a man whom she never imagined she’d see.

Sidner had returned to 38th street and Chicago avenue — the intersection where Floyd was killed — and was interviewing a nurse who had attended to someone injured after a truck had driven through the protest.

“The police chief’s behind you,” the nurse told Sidner at the end of the interview.

“Excuse me?” Sidner replied.

She couldn’t believe it — a sight she hadn’t seen in her 12 years of covering protests in Ferguson and beyond. But there he was. Medaria Arradondo, the Minneapolis police chief himself. Sidner saw him rise from the very spot where one of his officers now stands accused of murdering George Floyd. Arradondo, it turned out, had been kneeling in prayer.

It was a remarkable moment, and Sidner wanted to get to the bottom of it. So she approached him, even though she believed the mission to get him on the record would ultimately prove fruitless, given that this was not a scheduled media engagement.

Sidner and her team stood aside as a local woman engaged with Arradondo — who had dozens of people gathered around him. After listening for a while, Sidner began asking questions. The exchange was good, in the estimation of her producer Jason Kravarik. So good that he wanted it on the air right away.

“We need to do this live,” Kravarik told Sidner.

Contact was made with the CNN control room. Only, they happened to be in the middle of a newsworthy segment in their own right — anchor Don Lemon was speaking with Philonise Floyd, the brother of George Floyd, and attorney Benjamin Crump. Nonetheless, Lemon threw to Sidner, and she was live.

The impromptu interview lasted roughly five minutes. At the end of it, Sidner noted that Philonise Floyd was on CNN’s air at that moment, watching what the police chief was saying.

“Is there anything that you would like to say to this family, who is in utter despair and grief right now?” Sidner asked.

Arradondo took off his hat, tucked it underneath his arm, and looked Sidner squarely in the eyes.

“I would say, to the Floyd family, I am absolutely, devastatingly sorry for their loss,” he said — his words, like Sidner’s, muffled slightly by a mask. “And If I could do anything to bring Mr. Floyd back, I would do that. I would move heaven and Earth to do that. So I’m very sorry.”

Sidner thanked the chief and ended the conversation. Lemon, though, couldn’t pass up the opportunity to have a member of the Floyd family speak directly with Arradondo — something no one in the family had done, at that point.

“I’m sure the producers were freaking out, ‘What’s he doing in there?!'” Lemon said, of his spur-of-the-moment decision to connect Philonise Floyd and Medaria Arradondo. “And I’m sure Sara was thinking, ‘What is he doing?!'”

But Lemon knew the importance of the moment.

“It seemed like a really great conversation to foster,” the anchor said — noting that Arradondo went on to meet with the Floyd family in person several days later.

The anchor told Sidner that Philonise Floyd wanted to ask a question.

“I want to know if he’s going to get justice for my brother, and arrest all the officers,” Floyd said. (At the time, only Chauvin had been charged.) “And convict them.”

Arradondo had already left and was promptly pounced on by other media. But Sidner had to get back in there. So she waded into what had become a full media scrum.

The CNN correspondent had trouble hearing with all of the background noise, but confirmed with Lemon what she’d picked up. Sidner was aware that Arradondo had not yet spoken with the Floyd family. And here she was, about to serve as a liaison between the two. The internal pressure was on.

“If I don’t do this justice,” Sidner thought, “I will never forgive myself.”

Lemon, though, was confident the segment was in good hands.

“Sarah is an absolute pro,” Lemon said. He added, “I knew that if anybody could do it, it would be her because she is incredible.

The correspondent fought through the scrum — with some of the reporters irritated that she had already gotten a lengthy one-on-one with the chief, and now wanted more. But she’d caught Arrodando’s attention by saying that the question was coming directly from the family.

“This is the Floyd family?” Arradondo asked.

Sidner confirmed that it was. And once again, Arradondo removed his hat as he answered the question. The substance of his reply did not resonate with Sidner as much as the gesture. Twice, he’d taken his hat off in deference to the Floyd family. She was moved.

Only, Philonise Floyd couldn’t actually see the chief. He had the audio feed, but didn’t have a monitor for the video. So Sidner relayed what Arradondo had done.

“He wanted to make sure to be respectful,” the CNN correspondent said of Arradondo removing his hat. Her voice broke as she addressed Philonise Floyd, who was in tears. She added, “I know … you are hurting. And I know it’s not enough.”

The segment lasted for five more minutes. Sidner stood stoically and did not speak for the rest of the time. When it was over, she briskly handed over her microphone and fled the scene. She went to a nearby stoop, sat down, and began to cry — with the echoes of the protests ringing out amidst the twilight.

CNN Correspondents Omar Jimenez and Sara Sidner (Courtesy of CNN)

For the better part of the last decade, Miguel Toran has traveled the world with camera in tow. Having been based in London, China, and India, the NBC News cameraman has covered conflicts far and wide. He’s documented clashes over ISIS territory in Syria, and even filmed in North Korea. A battle-tested pro, Toran encounters very little that fazes him.

It was decided that Toran would be moved stateside in early 2020. It was an election year, and so Toran figured he would get a respite from the war zones where he frequently toiled. Yet sure enough, instead of hitting the campaign trail, the cameraman found himself on the streets of Minneapolis during the last weekend of May.

“I thought by now I’d be covering political rallies or primaries,” Toran said. “I didn’t think I’d be covering unrest in major cities.”

But duty called, and so, on Saturday May 30, Toran ventured out in the field with MSNBC host Ali Velshi — a reporter with whom he’d previously teamed up overseas. (“We have a very good rapport,” Velshi said.) A sound tech, a producer, a tech manager, and three security personnel rounded out their crew of eight, as they headed for the Whittier section on the east side of town to document the festering fury.

An 8 p.m. curfew had been enacted in the Twin Cities for that Saturday night. The same edict was in place the night before, and proved ineffective. On Saturday, the police stepped up their enforcement tactics.

The streets were still packed at 8:45, well past the curfew. Velshi and Toran both describe the march as peaceful. But police sought to disperse the crowd nonetheless. They showed up in riot gear, and ordered protesters to clear the streets.

Velshi, Toran and company were on the move with the rest of the crowd, but paused for a live shot on Nicollet avenue, between 24th and Franklin streets. The protesters, at this point, were scattered. But those who remained started up a chant.

“GEORGE! FLOYD! GEORGE! FLOYD! GEORGE! FLOYD!”

The chant grew louder. Toran aimed his camera at a shirtless man who approached a line of police, chugged from a gallon of milk, then threw the container on the ground. And then the cops started firing rubber bullets.

“AH SHIT!” Velshi cried out. He’d been hit.

Toran whirled the camera around to zero in on Velshi, who grabbed his left leg in pain. Because he was looking through his viewfinder, his peripheral vision was limited. And so he didn’t see police officers preparing to shoot the rubber bullets. Velshi backed up against a car, and Toran approached the reporter to make sure he wasn’t hurt too badly.

Rubber bullets weren’t the only danger. The cops were now firing tear gas, and the crew of five was forced to run. All the while, Toran kept rolling. And for much of their dash through the streets of Minneapolis, the images he was filming were going out live — something that was a broadcast impossibility not too long ago.

“The way we are covering demonstrations now, you couldn’t do it like five or six years ago,” Toran said. “Because before, you had to be near a satellite truck… on the outskirts of the demonstration. You had to be hooked up into the satellite truck.”

Now, thanks to cellular bonding backpacks, Toran and crew are no longer tethered to a satellite truck, and can go wherever they want to provide viewers with a more immersive experience.

But as the man wearing that backpack while also toting a heavy camera, Toran says that the technological advances have made protest coverage a much more physically daunting task than it used to be.

“For us, it’s hard,” Toran said. “You are on air maybe for three, four hours — and you are constantly on air. When the correspondent is not live, you are still on air… You are carrying that big camera on the shoulder, all your batteries, the transmission on the backpack. And then you are walking. Some days [in Minneapolis], we were walking eight, 10 miles.”

Yet they didn’t stop moving. Even after being struck by the rubber bullet, Velshi wanted to keep going. His security chief, Evan Minogue, was on the phone with the bosses at NBC literally seconds after the correspondent had been hit. The tendency of security, by design, is to go about the job more cautiously. So Velshi and crew were given the option to either continue reporting, or head for safety. The journalists didn’t hesitate.

”My team and I elected to keep on going,” Velshi said. “We were in it at that point.”

“They try to keep us safe,” Toran said. “And always, the journalist and the cameraman want to go closer than the security feels like it’s safe to go. So you’re trying to find a balance.”

Velshi, like his cameraman, has been in tough spots before. Hurricanes, conflict zones, mass shootings. But that night stands out, in Velshi’s experience, because he had not envisioned a scenario where police would be firing tear gas and rubber bullets during what he says was a peaceful demonstration — even after the crew had identified themselves as media.

”We all go through various types of training to prepare us for these things,” Velshi said. “Being taken hostage, crowd control issues. We weren’t prepared for the police response, largely. That’s not something they teach us in America to be ready for.”

Velshi pushed through the pain — which he says was worse a few days later than it was that night — and stayed on the air for several more hours. The reporter noted and appreciated the outpouring of support he received after having been struck by the rubber bullet, but wishes more people recognized the dangers by the people they don’t see on TV who also put themselves in harm’s way to bring viewers the story.

“I’m almost embarrassed by the tweets I get from people talking about how it’s heroic work. It’s not heroic work. I mean, we’re just doing what we do,” Velshi said. He added, “I had a team out there, all of whom faced exactly the same thing I did. I just happened to get hit. It was just chance that I got hit over anybody else. And they just keep doing their job all the time. And no one will ever know their names.”

But that’s perfectly good with Miguel Toran. Above all, it’s the importance of the job that fulfills him.

“I think it’s fine that we stay behind-the-scenes,” he said. “And that people don’t think about the work we do.”

MSNBC Host Ali Velshi and Cameraman (Courtesy of MSNBC)

Ninety seconds.

That’s all a field correspondent has, often times, to tell their story during a live shot.

For a subject as complex as the George Floyd protests, a minute and a half is just not enough.

“I cannot explain racism in 90 seconds,” said Fox News correspondent Bryan Llenas.

Impactful work can take a little more time than a reporter on the ground is generally given. But during the protests, the usual time constraints were relaxed. Correspondents routinely kept on talking, narrating what was happening in front of them. Camera operators continued to roll for five, 10 minutes at a time, or more.

On Saturday May 30, Bryan Llenas and his cameraman Oleg Vernik — stationed at the intersection of Bedford and Snyder avenues in Flatbush, Brooklyn, where a protest was about to get violent — were asked to keep their segment going for nearly 15 minutes. Anchor Jon Scott interrupted only sparingly. For the most part, it was Llenas, and Vernik, and the sights and sounds of a scene rapidly descending into chaos.

Protesters attacked two NYPD vehicles, leading to a line of police charging at the demonstrators. The protesters hurled bottles and rocks at police. The cops fired back with mace and pepper spray, and even broke out their batons. The protesters edged closer. Sirens wailed in the background. The situation was about to explode.

Enter a nurse.

The public’s admiration for nurses has grown dramatically in the past 100 days. And here, again, was a nurse putting herself in harm’s way so she could help.

The nurse, a Black woman, stood between the protesters and the cops — who were, at that point, almost within arms-length of each other. The nurse was pleading with the protesters to back up.

The woman caught Llenas’ attention. He decided he had to get close to her.

”I’m seeing it with my own eyes,” Llenas said. “We point Oleg to the woman. And constantly, I’m trying to find myself and position ourselves in between the police and the protesters, because I think that’s the best place to be to show what’s happening. And you could see, in the middle, this fearless woman, just trying to de-escalate the situation and tell the people to calm down while also negotiating with police.”

Her efforts were working.

“Don’t give ‘em the satisfaction!” She said to one man. And sure enough, that man, and the other demonstrators, began to retreat.

Knowing when not to talk is an underrated broadcaster skill. Llenas recognized that the moment called for him to say as little as possible.

“I wanted to just let people at home hear her and see her do this,” Llenas said. “And we did. For a moment, you see me just stay quiet. And I made sure Oleg zoomed in on this woman and what she was doing.”

What she was doing, almost singlehandedly, was keeping everybody safe during a volatile situation. The protesters — at one time less than three feet away from the cops — had backed up almost 50 feet.

“Black people are not dying no more! That’s it! That is it!” The nurse said, to cheers from the protesters.

The protesters locked arms as the woman continued addressing them. Llenas and Vernik momentarily turned their attention to a nearby police SUV on fire, and tried to approach.

“Back up!” An officer ordered. “Back up!”

Firefighters tried to extinguish the blaze. Meanwhile, objects continued to be hurled at police — who were now lined up diagonally at the intersection and fully surrounded. A fire extinguisher was thrown at the officers.

But the nurse continued imploring the demonstrators.

“Please back up! Please back up!”

Llenas, at that point, had watched this woman try to calm everyone down for more than 10 minutes — with hundreds of people in the area, a fire in the distance, and tensions about to blow.

”And that’s when I said, you know what? Let me just go in there and see if I could ask her a question.” Llenas said.

So he and Vernik approached. And the nurse was happy to talk with them.

“I see that you’re trying to calm people down,” Llenas said to her. “What’s your message to them?”

“Protest peacefully,” she said. “Don’t protest and give the officers a reason to arrest us! A reason to kill us! Enough is enough! Protest peacefully.”

Just then, Llenas was informed that the stirring sequence had to be interrupted. Jon Scott, back in the studio, was up against the top of the hour, and had to hand off to Bill Hemmer. But soon after Hemmer reset the scene at the top of the hour, he went right back to Llenas. And Llenas went right back to the nurse.

“Violence is not the key all the time,” she said. “Violence is not the way to go. The NYPD has their job to do, and so do we. As Black people in this Black community, we have to understand that the police have a job to do. We can protest, and protest peacefully. All this burning down stuff is not called for.”

The nurse’s actions have stayed with Llenas ever since.

”I think she was emblematic of people in the neighborhood who understood the pain and the frustration of her neighbors and her community, but did not want to see more her friends and families and neighbors get hurt from that,” he said.

Sometimes, even 15 minutes is not enough to tell a story. But other times, just one moment captures it perfectly. To Llenas, that last exchange with the nurse was extremely important. He thought it crucial to have her explain why she’d spent the past 15 minutes putting herself in danger to keep the peace.

”It was a beautiful moment,” Llenas said. “A raw, authentic moment.”

And there was one more reason that the nurse resonated so strongly with him. A reason that went unspoken on the air, but was at the top of his mind just the same. For, just like the nurse working on the front lines of New York’s hospitals, Bryan Llenas had personally been touched by Covid-19.

Fox News Correspondent Bryan Llenas (Courtesy of Fox News)

Part II: Coffee Cans and Yarn

Two months earlier, on April 1, Llenas was doing a standup outside a New York City firehouse for The Daily Briefing with Dana Perino. The segment seemed straightforward enough, on the surface. Llenas was reporting on the overtaxing of New York’s 911 system in the early weeks of the coronavirus pandemic.

But then, all of a sudden, he began to choke up.

“My grandmother lives on the Upper West Side, she’s 85-years-old, has pre-existing conditions. She’s tested positive for Covid-19,” Llenas explained. “And I understand, the thing is that when you know and love somebody that has Covid-19 it’s a real emergency to you. So I called 911 to get an ambulance there, she was by herself, and they picked her up. But it took a lot longer than it should have.”

Llenas says that his grandmother, Rafaela, ultimately conquered her month-long battle with the virus. But not without several scares. There were multiple calls to 911, multiple visits to the hospital. All the while, Llenas had a job to do — even as he helped arrange her care.

The correspondent recalled one occasion, shortly after the March 30 arrival of the U.S.S. Comfort, where juggling professional and personal responsibilities seemed overwhelming.

“I had about four or five live shots within a four-hour span,” Llenas said. “And as I’m sitting in a rental car in the front seat, and conducting a Zoom interview with a business owner in North Carolina, I’m also listening to a press conference. And at the same time, I’m texting with my uncle who’s taking care of my grandmother in Washington Heights. And I’m trying to coordinate with two or three other people to get her an IV drip, because I know that she’s really dehydrated in the apartment, and I can’t get her help.”

“And I’m calling, and I’m texting. And in between live shots, I’m running to the camera, running back into the car, and I’m on the phone with my grandmother. And there’s also a language barrier, so I’m speaking Spanish and English.

Llenas called the experience “one of the hardest things I’ve ever had to do in this job.”

The emotion in Llenas’ voice during that April 1 Daily Briefing live shot becomes much easier to understand, given the context of his grandmother’s battle. And it resulted in a memorable three-minute on-air sequence. But, by coronavirus era broadcasting standards, it was actually one of the more run-of-the-mill segments overseen by Megan Albano — executive producer of The Daily Briefing.

Putting on that hour-long program each day has become far more difficult in the era of Covid-19. The anchor, Dana Perino, is working from home. And what was a 12-person control room is now down to five. Albano is stationed in a separate control room from other members of her team. Communication, as a result, becomes more challenging.

”I’m in one control room, my line producer’s in another control room, and it’s not as easy just to turn and say, ‘Hey, are you able to get that graphic made?’” Albano said. “You have to get on the bridge. You have to call. And so there is an added level of communication that obviously in breaking news you’d prefer wasn’t there.”

There are also uninvited guests. Just as young children and animals have become fixtures at videoconference meetings across America, so too have they become a regular part of cable news. One notable pet intrusion happened on the May 1 edition of The Daily Briefing, when a dog owned by guest Donna Brazile began barking relentlessly. But despite the interruption, Albano had no thoughts about shutting down the segment.

“It’s part of what makes all of this so real,” Albano said. “People at home who are working and have kids or their own dog can appreciate that. You try to put your dog in a place where he’s not going to bark, or you try to tell your kids, ‘Okay. I’m jumping on a call for 15 minutes. Please be quiet.’ And you just sit there and you pray.”

It’s one thing for a guest to be interrupted. Worst case scenario, the segment can always be scrapped. But the stakes are higher for an anchor. There’s no easy fail safe option if the anchor is unable to broadcast. Which is why Harris Faulkner holds her breath when her daughters take their lunch break from school.

Faulkner helms Outnumbered and Outnumbered Overtime in her basement from 12 to 2 p.m. each day. Her 11 and 13-year-old daughters — like most schoolchildren in America — have been taking online classes during the pandemic. And their lunch break falls during the time when Faulkner is on the air. Sometimes, the children banter about the menu. And their mom, through the ceiling, is able to pick up on what they are saying.

“I don’t know if the audience can hear it… I can hear the discussion during the commercial!” Faulkner said, laughing. “I’m like, ‘Girls! Can we discuss the sour cream later?!’”

Overall, though, Faulkner has found the visual distractions more difficult to overcome than the rare audio intrusion. The anchor has taken over her husband’s man cave for her broadcast. Commandeering that space required a treasure trove of sports memorabilia to be relocated. A Kansas Jayhawks dartboard. A framed photo of Magic Johnson and Michael Jordan. A shot of Faulkner singing the anthem at a Tampa Bay Buccaneers game. All of it gone — sacrificed for the construction of a makeshift studio.

The centerpiece of the room is now a 75-inch screen turned on its side — which serves as Faulkner’s backdrop. That screen is programmed to look just like she’s on set at Fox News. But a screen saver kicked in at a rather inconvenient time on March 24 — as Faulkner was about to interview President Donald Trump as part of a virtual town hall.

“Wait! Hold it!” said Alan Komissaroff — a Fox News VP producing the broadcast — in Faulkner’s ear. “She’s standing in front of the Bahamas!”

“It was palm trees blowing in the wind,” Faulkner said, describing the image.

Fortunately for the anchor, Trump diverted attention away from the glitch — making headlines by talking about a potential reopening of the country on Easter Sunday.

“He was making so much news, nobody saw Bahamas,” Faulkner joked.

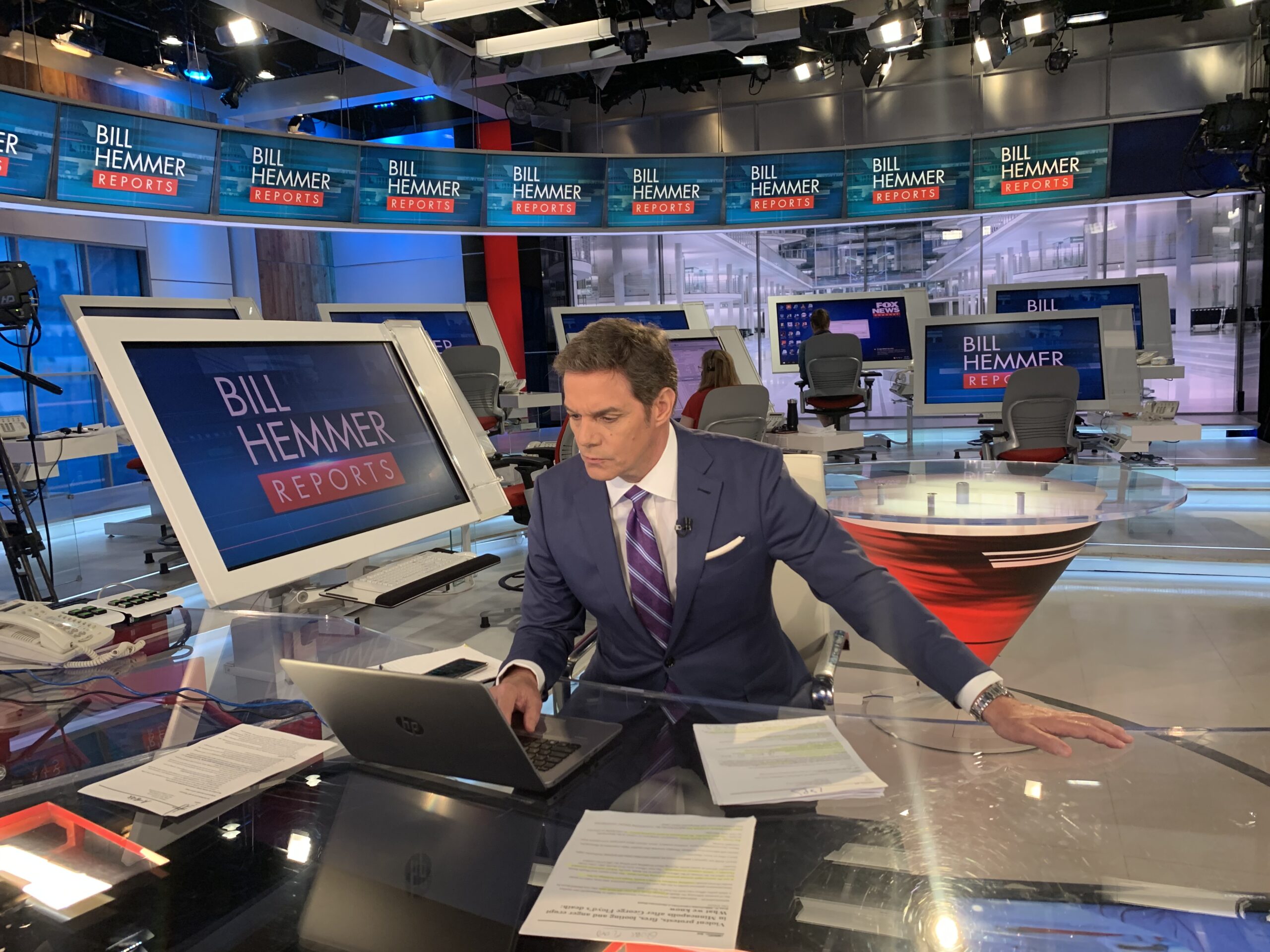

Minor hiccups aside, Faulkner’s home studio experience has gone rather smoothly. But not all anchors have gone that route. Faulkner’s afternoon colleague, Bill Hemmer, has opted to continue broadcasting from Fox News headquarters.

“I’ve been coming into the office 90 percent of the time during this,” Hemmer said. “And that was my choice … I thought it was important to show that it was okay to come in here.”

Instead of Bahamas screensavers, viewers of Bill Hemmer Reports in the 3 p.m. hour had grown accustomed to seeing a beehive of activity taking place behind the anchor. The state-of-the-art Fox News Deck from where the broadcast originates had — prior to the virus — been packed with staffers working at massively large terminals. Now, the audience sees Hemmer, and not too many others.

”I will go in the studio and there will be two people there,” Hemmer said. “Two months ago, we had 15.”

Hemmer believes his team has adapted well, and that the broadcast doesn’t feel much different than usual.

“You adjust your expectations… I think that’s that’s where we are,” Hemmer said. “And unfortunately, I think that’s the way it’s going to be for some time.”

But the anchor admits that on occasion, the solitude can get to him.

”I will say, there is… an emptiness.”

Fox News Anchor Bill Hemmer (Courtesy of Fox News)

Feelings of emptiness amid the pandemic are, of course, not unique to cable news personalities. Like so many during this time, they have stayed away from their offices and been separated from their professional colleagues. And as it happens, they have coped with their newfound isolation just as much of the nation has — by turning to family.

MSNBC anchor Stephanie Ruhle may not have her usual team in place while she’s away from 30 Rock, and working out of a room above her garage. But her three children are all eager to stand in for the regulars and help their mom while she’s on the air.

“That’s a very Stephanie thing to do, to put her kids to work,” joked Lauren Peikoff, Ruhle’s executive producer. “She’s super engaging with them, and they’re a part of all the things she does in her life.”

Ruhle’s pint-sized crew consists of a producer, a copy editor, and a makeup artist.

“My son of 11 will comment on my grammar,” Ruhle said. “And my son who’s 13 will complain… If I get worked up on TV, or I’m moving my hands too much, or I’m too loud, he’s like, ‘Ugh… not so hot.’

“And then my daughter, who’s seven, is helping me with hair and makeup.”

The anchor’s daughter is the captain of what Ruhle calls her “glam squad.” And she gets her job done even in the middle of a live broadcast.

”She will run next door — she knows not to open the door while we’re on,” Ruhle said. “Tap, tap, tap. And then during the commercial, a little hand will come through the door with lip gloss.”

But the most rewarding part of working with her children, for Ruhle, has been watching them grasp the importance of what they are doing.

“All of them take the story really seriously,” she said. “I know it’s hard for kids to do. A lot of kids who are home are like, ‘Why am I home? Can I just go back to school?’ But because I’m experiencing so much of it, my kids are too.”

Ruhle wasn’t the only one at MSNBC who relished the chance to spend more quality time with her family. The transition to home setups allowed Dan Arnall, executive editor of MSNBC Dayside, the opportunity to reunite with his wife and daughter after a long time apart during the early stage of the pandemic.

“I hadn’t seen my family for, at that point, it had been about four weeks,” Arnall said. He added, “It was a little bittersweet leaving 30 Rock. But I was very excited to know we were going to be back together as a family.”

The reunion with his loved ones was facilitated by an abrupt phase out of operations at the network’s legendary headquarters in Manhattan. In the early stages, there was hope among the staff that they could go about their routines as usual.

”When we started the process, it was, “How do we keep people safe? Do we need to have more Purell dispensers put up in 30 Rock?’” Arnall said.

But everyone in the building soon realized hand sanitizer wasn’t going to be enough to keep them in business.

“Within days, it [went from] ‘How are we getting a guest make up?’ to ‘No more guests anywhere in our facilities.”

Normally, according to Arnall, 106 people are involved in the production of dayside programming on MSNBC during a given weekday. By early April, all but two — Arnall and just one producer — had abandoned 30 Rock. The dayside editor longed for company.

“The kind of bustle of a big bullpen-style newsroom — which is loud with conversations about the editorial, people talking about this and that, phones ringing constantly — It was kind of profoundly familiar and loud,” Arnall said.

Betsy Korona — executive director of news for MSNBC — likewise misses the pre-virus dynamic.

“When you’re hashing out a script together, or you’re brainstorming an idea, being able to see each other’s faces and just kind of pile on, ‘Oh, yeah. And what if we did that?'” Korona said. “There’s a cadence that you have when you work together in a room. I think that took a little bit of adjustment.”

Adapting to the lack of face-to-face contact requires more than a little ingenuity on the part of MSNBC’s technical team. Arnall has adopted a mantra from the movie Apollo 13 to inspire outside-the-box solutions from his staff.

“I don’t care about what something was designed to do. I care about what it can do.”

The team’s adherence to that credo has kept Arnall from having to utter that far more well-known Apollo 13 quote — Houston, we have a problem. Instead, the MSNBC newsroom has been full of solutions.

“We’ve all become insanely resourceful,” said Peikoff.

Indeed, there’s no greater testament to that than Ruhle… and staff.

“My middle son… we have a camera in the car with us,” she said. “And we were out buying fish one day. The fishermen where I live, the boats came in. And we went and shot it. He was my sound guy.”

MSNBC Live Anchor Stephanie Ruhle (Courtesy of MSNBC)

“How are we going to keep the four networks all on the air? And how do we get people the hell out of the buildings?”

Those were the questions facing Jack Womack, CNN senior vice president of operations and production on March 11. He was the man charged with making sure that not only CNN, but also CNNi, CNN En Espanol, and HLN all remained fully functional. And he was also responsible for clearing out broadcast centers in New York, Atlanta, and elsewhere.

Step one? Laptops. CNN dished out more than 500 computers to its employees over the course of nine days. Only, the company couldn’t purchase enough in the necessary timeframe, so they had to rent some to fill the void.

Then, Womack’s team went about the task of setting up the home studios. They reached out to Cisco Systems for consultation on how to get the anchors set up in their houses. As a backup, the network also built emergency studios at an alternate New York City location separate from their Hudson Yards headquarters, and at a conference center in Washington belonging to their parent company AT&T.

All of the scrambling during the first few weeks of the pandemic was designed solely to keep the signal going out by any means necessary. By early April, Womack and his team felt they had the operation under control.

“Things have stabilized to the point where it’s not a crisis every minute,” Womack said.

That, of course, is not to say there weren’t bumps in the road. While connection with the hosts and correspondents has been mostly effective, hooking up with guests can be a bit trickier. Sometimes, the technological gods decide not to smile upon a particular guest’s appearance. Other times, a segment could fall prey to an OK Boomer moment, or other form of pilot error.

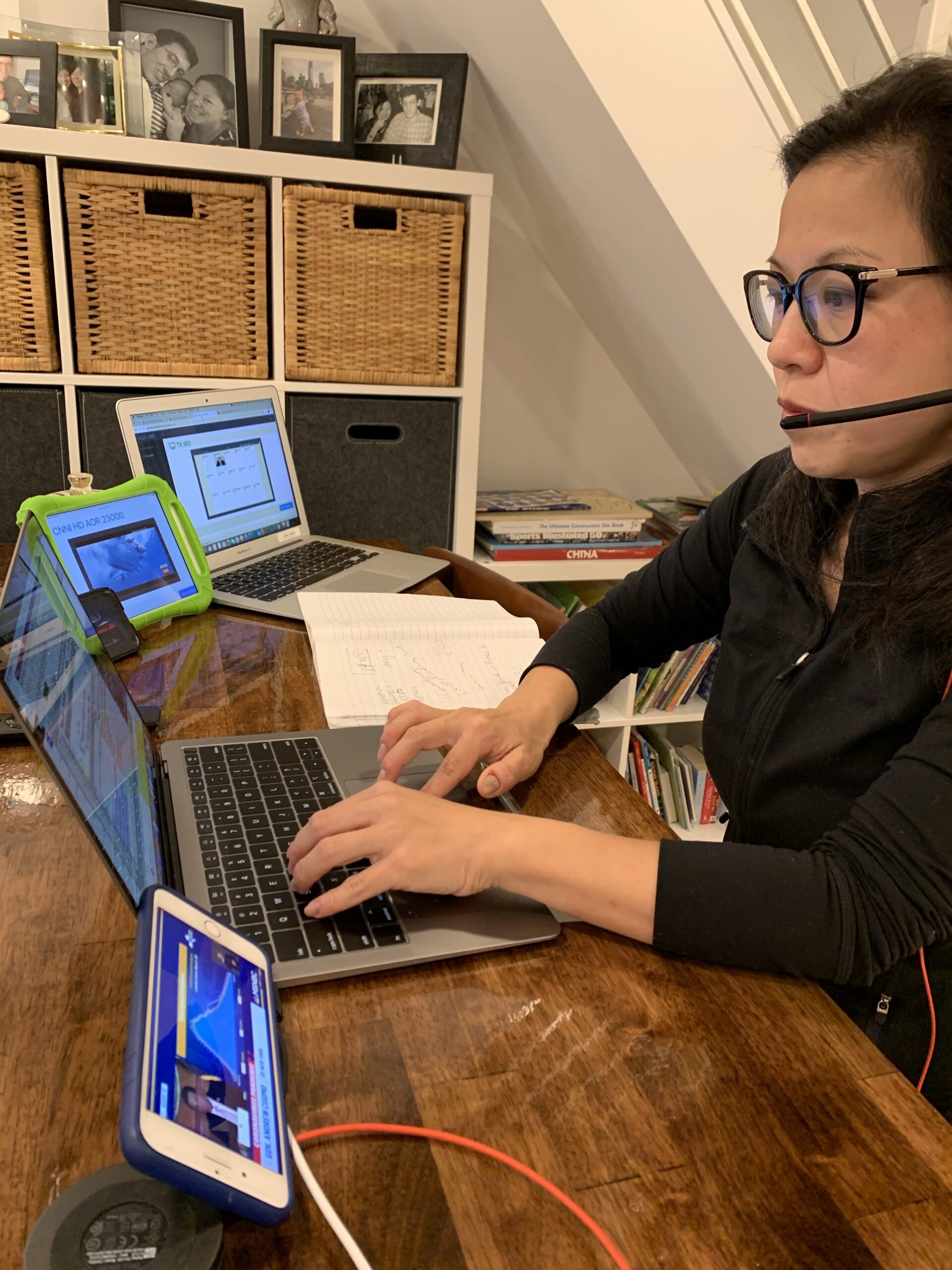

“We’ve had more… phoners than we’ve cared to,” said Susie Xu, the executive producer of Erin Burnett: Outfront. “People’s shots go down, or they can’t figure out how to use Cisco or Skype — no matter how long we’ve been trying to talk them through it.”

One guest who did connect for a particularly memorable segment was Bernard Shaw — the retired CNN anchor and cable news legend. Shaw happened to be booked for an appearance on Outfront June 1 to celebrate the network’s 40-year anniversary. Only, that was the night that protesters outside the White House were tear gassed and President Trump marched from his residence to St. John’s Episcopal Church — where he posed for photos while holding up a Bible.

“You want to cancel this?” Shaw said. “Because you’ve got a lot going on.”

“Absolutely not,” Xu said. “This is a moment. We want you to weigh in on this.”

Xu’s instinct to keep him on as scheduled paid off as Shaw — a man not known for hyperbole — went on to deliver a stinging, authoritative take on the bizarre events transpiring before him.

“Holding up that Bible would have made P.T. Barnum proud,” the famed anchor said.

The entire, surreal sequence of the president’s photo op outside St. John’s certainly ranked toward the top of CNN’s list of the most compelling breaking news segments since the start of the pandemic. But the No. 1 spot on that list, without question, belongs to the live arrest of CNN correspondent Omar Jimenez and his crew members in Minneapolis — arguably, one of the most shocking real-time segments in recent cable news history.

CNN anchor John Berman was quarterbacking, along with his New Day co-host Alisyn Camerota. The stunning events were transpiring at warp speed. Berman’s priority, as he watched his colleague get handcuffed on camera, was to shepherd viewers through the frantic moments as best he could.

“When that happens, there are a million things that race through your mind,” Berman said. “I always think it’s your responsibility to try to slow it down for the audience. There’s nothing wrong with repeating what’s happened, bringing them up to speed. There’s nothing wrong with silence, in some cases, so they can watch and learn for themselves. And there’s nothing wrong with being transparent about what you don’t know.”

And there was quite a lot the CNN team didn’t know in those fraught early moments. The flow of information was more sluggish than usual — given the fact that the New Day operation was scattered across various control rooms and home studios, and not centralized as it usually is in New York. That constraint made it crucial for Berman to relay information to viewers just as soon as he got it.

“We got word that CNN management had made contact with [Gov. Tim Walz (D-MN)], that was the first bit of information that we got,” Berman said. “I have a computer on my desk right next to me, and I got … an e-mail. It said, ‘Hey, this happened. We can report X.’ So you read out loud.”

New Day did not take a commercial break for more than an hour. All the while, Berman and Camerota remained on the air. And roughly 90 minutes after being taken into custody, Jimenez and his colleagues were released, and the correspondent was back on the air — doing a live shot recounting his experience.

It all happened seamlessly. Thanks, in large part, to the behind-the-scenes team — whom Berman lauds as the “technical marvels.” The same technical marvels who have kept him and Camerota on the air every day since the middle of March.

”Somehow we didn’t miss a beat,” Berman said. He added, “It’s an honor to work with the people who figured out how to get us on TV with coffee cans and yarn.”

Erin Burnett: Outfront Executive Producer Susie Xu (Courtesy of CNN)

Part III: The Guardian Angel

It has been exactly 100 days since March 11 — the date when the nation changed forever. That night, Americans who might have been ambivalent about Covid-19 received an unmistakable warning about the severity of the pandemic when — in the span of an hour — actor Tom Hanks announced his diagnosis, the plug was pulled on the NBA season, and President Trump gave a sobering White House address.

In the past 100 days, more than 115,000 Americans have died from the coronavirus. Nationwide protests have erupted over the killing of George Floyd. Unemployment, despite a rosier May than expected, remains well over 10 percent.

The gravity of these times are not lost on cable news personalities. Talk to someone in the industry, and inevitably, they will mention a deep sense of responsibility about their work. The importance of providing this public service at this time.

“This is why we do this,” said Stephanie Ruhle. “We’ve got to help our viewers… I know this is hard, but it’s why we chose to do this. It’s an honor. It really is.”

But while they are serving their audience, cable news personalities themselves are not immune to the perils of the world. Right now, they are going through what everyone else is going through. How much of that should a reporter let in? How close should they get to what they are covering?

”You want to open the aperture enough to let enough of the story in that you can feel it so you can tell it well” said MSNBC correspondent Garrett Haake. “But not so much it overwhelms you. … If you if you let too much of it in while you’re still in the thick of it, I think it makes it harder to do the job.”

That can be an extraordinarily fine line to walk in these unusual times. Take the experience of Fox News correspondent Kevin Corke. On Saturday June 6, Corke saw what he estimated to be 100,000 demonstrators marching down 16th street. He was moved by the mass of people united by a common cause.

“I’ve covered tragedies and I’ve covered triumphs,” Corke said. “But to see that that sort of solidarity was really powerful for me because it spoke it spoke to me directly. Sometimes in life, it’s not just about an individual. It’s about all of us.”

And that, too, is a common refrain of cable news personalities in the post-Covid era. Never has there been more talk of industry cohesion, of coming together for the greater good.

Lest you write off this party line as hollow, consider the recent experience of CNN correspondent Bill Weir. While out covering a protest in Brooklyn, Weir was interviewing musician and activist Jon Batiste. But Weir’s cameraman Evelio was in a tight spot amongst the protesters — fully exposed while walking backward and filming the interview.

A woman came to their rescue. She extended her arm and shielded Evelio and the rest of Weir’s crew. Weir completed the interview without incident to his team.

After they wrapped, the woman introduced herself.

“I work for Fox & Friends,” she said. “But we’re all on the same team today, right?”

“I was wondering who our guardian angel was!” Weir replied.

The woman, Fox & Friends booking producer Bridget Gleason, said she didn’t hesitate to help out a crew representing a broadcast rival.

“It’s their job to get the message out,” Gleason said. “And I just wanted to make sure, even though they were from another network, they could do their job.”

And therein lies a symbol — one which demonstrates the passion of the reporters and crews working these historic stories. These network teams have spent the last 100 days under fire. But they don’t mind. All they can think about is Day 101.

• • •

Joe DePaolo is a Senior Editor for Mediaite. KJ Edelman is a Reporter for Mediaite. The reporting for this article was done by DePaolo and Edelman. It was written by DePaolo, and edited by Mediaite Editor in Chief Aidan McLaughlin.

Have a tip we should know? tips@mediaite.com