WRC Lets Kids Ask Coronavirus Questions

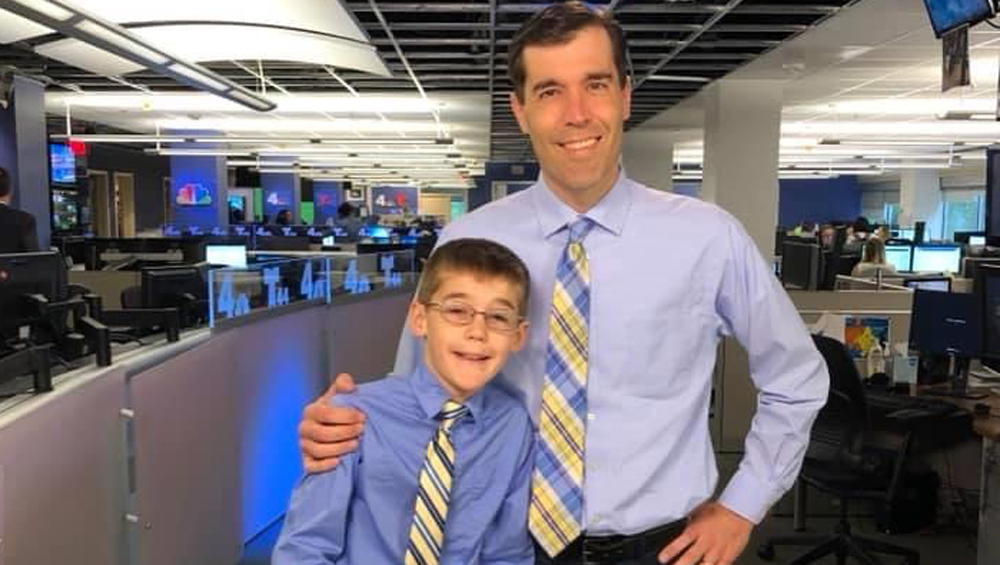

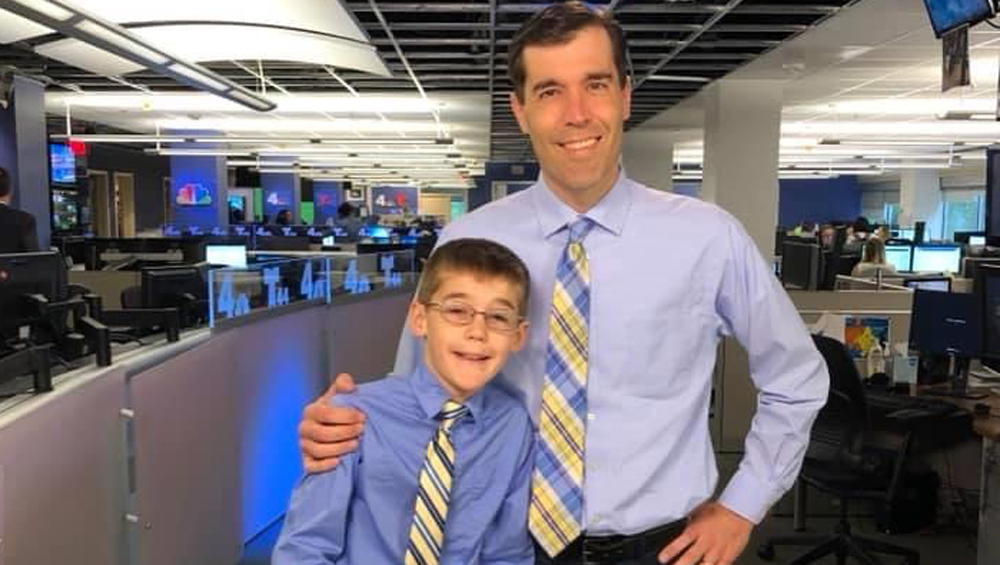

WRC Washington’s Scott MacFarlane isn’t just reporting on the coronavirus pandemic but sheltering through it at home with his wife and two young kids. Not long ago, he was watching the news with his nine-year-old son, who wanted to know what was going on.

“What he was watching on cable news and local broadcast news disturbed him,” MacFarlane says. “I could see it in his eyes. I could hear it in his voice. I didn’t think it was appropriate for him to keep watching, and that bothered me.”

At that point, other organizations had yet to launch any kid-oriented coronavirus newscasts (NBC News has since done so). “The only way for him to get that would be if we figured out a way to offer it to him,” MacFarlane says. “With him in mind, I sketched out a concept.”

That idea, News 4 Kids, is now heading into its second week on NBCU-owned WRC, where it airs Saturdays at 12:30 p.m. and Sundays at 5:30 a.m., along with selected segments archived online.

The show was fast tracked from concept to execution within a week and follows a simple format: Kids submit questions via Skype, Zoom or FaceTime. Reporters, including MacFarlane, chase down the answers. Morning show co-anchor Eun Yang hosts and pulls it all together.

The idea is simple, but the psychology underwriting it is more complex. In fleshing out how the show would be executed, MacFarlane spoke with a pediatrician (Dr. Christina Johns, who has since become a recurring source for the show), a school psychologist, officials from the city and state departments of education and even a pre-school teacher to get a range of perspectives.

“What I heard consistently was kids want to be heard,” he says. “They have been getting a lot of instruction about you can’t do this, you can’t do that, but I don’t think kids get to be listened to enough.”

The concept was democratic. The kids ask what they want without adult guidance or direction. “Whatever we can find answers to, we will,” MacFarlane says.

Some questions, he found, were impossible to answer, such as the five-year-old who simply wanted to know when all of this will end. Others can yield more specific responses, such as the 17-year-old who wanted to know about the fate of graduation.

MacFarlane and colleagues solicited questions through networks in all corners of the community, aiming for age, geographic and socioeconomic diversity in the questioners. The results he got were revelatory.

“The questions from the kids are things we should have been asking weeks ago and chasing down,” he says.

Like what will happen to this year’s yearbooks, for example. “I mean, they are for elementary and middle school, and it is a big thing for a high school senior to have a yearbook,” MacFarlane says. “We had two or three kids ask that same question.”

Certain questions are tougher than others, such as the 10-year-old who asked, “Is summer canceled? My family always goes to the beach. Can we not go to the beach this year?”

MacFarlane didn’t know the answer. “And we should start thinking about that because that is an emotional connection kids have, and it could be incredibly disruptive and disturbing to tell a kid, ‘Probably not,’ ” he says.

So MacFarlane checked with the mayor of Ocean City, Md., one of the area’s biggest beaches, to find out the chances. The mayor’s response: Beaches are closed through April, but they’re still holding out hope for summer.

Other questions are more pragmatic and allow MacFarlane and the other reporters to bring in some high-profile experts for answers. One was from a high school freshman who wanted to know how she could be ready for fall sports now that her spring season was canceled, and summer camps were dubious. Retired athletes Etan Thomas from the Washington Wizards and Brian Mitchell from the Washington Redskins helped give her answers.

In relaying those answers, tone is everything. Yang, the show’s host, is a parent herself with teenagers at home. She knows that striking the right tone with her younger audience is crucial to pulling the show off.

Eun Yang hosts WRC’s News 4 Kids

“I have never spoken down to my children even when they were very little,” she says. “The tone has to be something of a balance. The kids are smart. They are informed. I want to answer them in a straightforward but conversational way.”

Empathy drew Yang into being part of the show, both with the kids it’s aimed at and the parents who are now with them 24/7.

“We are trying to figure out our new normal at home, and that has been very difficult,” she says. “We are trying to manage our own mental well-being” while working an even more demanding work schedule than ever, managing the kids’ distance learning, refereeing arguments between siblings and turning over each day’s meals and laundry.

Yang says her own kids had a tough early adjustment into social distancing and have been feeling keenly the absence of their friends and grandparents, who live nearby. “Now they get it, there is no more argument,” she says of the need to self-isolate, though it doesn’t diminish her kids’ pangs of longing for others’ company, even for the schools they now miss.

“It goes to show us how important school is not just for academics, but for what it teaches you about communities, friendships, structure and relationships,” she says.

MacFarlane says local TV can at least play a small role in commiserating over all that kids have lost.

“They are getting their moms and dads constantly telling them don’t do this, don’t do that, don’t touch this, don’t leave the house. They are not being heard, though,” he says. “Our mission, really, is to listen to them.”

Comments (0)