On the evening of Sunday, Sept. 23, 1962, millions of American families finished their dinners, turned on their televisions and were introduced to The Jetsons, a cartoon sitcom produced by the legendary team of Hanna-Barbera. Set in 2062, The Jetsons captured the technological optimism of the time and projected it into a space-age, gadget-fueled vision of the future, inviting its viewers to imagine the dazzling possibilities that the current wave of technological achievement could one day realize. (Jetsons afficionados believe George Jetson was born July 31, 2022, though it’s not clear that’s canon.) In the end, The Jetsons was a rather tame, pedestrian sitcom about a family that reinforced traditional gender and family roles, knew little of the social issues of the time (it was, for example, unbearably white), and effectively glorified the consumerist, suburban lifestyle. But as a template for a technology-driven American future, it was no less than iconic. It was also prophetic.

The Jetsons debuted five years after the Soviets had launched Sputnik, four years after the opening of the first commercial nuclear power plant in the U.S., and 16 months after President John F. Kennedy set a goal of putting a man on the moon by the decade’s end. Fifteen years earlier, scientists at AT&T’s Bell Labs invented the transistor, and soon after, miniature (by contemporary standards) transistor radios were found in many households. That same year, the Levitt brothers broke ground on their first Levittown suburb in Nassau County, New York. The team at Hanna-Barbera extrapolated from all of these trends and created a slick (albeit goofy at times) rendering of a future world. The world of The Jetsons seemingly occupied a middle layer between the Earth and outer space, with buildings and developments either high up on stilts or floating in air. The architecture and interior design could be described as cartoon-Saarinen, inspired by the swooping curves of the architect’s designs for the terminals at Dulles and JFK airports and his fabled tulip tables and chairs. Technophilic names—from the family dog, Astro, to Cosmic Cola and Molecular Motors—were omnipresent. Even the teenage heartthrob was named “Jet.” (“Lectronimo,” the nuclear-powered robotic dog, was a bit of a head scratcher, though.) In this respect, the series was a full-throated embrace of the technologies upon which the new world would be built.

There is an optimism at the heart of The Jetsons. The nuclear fission borne from the Manhattan Project contained an astonishing power that ended the war with Japan and had since been transformed into a seemingly magical source of everyday fuel for the growing economy and new household capabilities. Rockets had blasted Alan Shepard, followed by Gus Grissom, John Glenn, and Scott Carpenter, into space. Televisions were starting to broadcast in color. And Moore’s law, which held that the density of integrated circuits would double every two years, was beginning to manifest (even if it had yet to be articulated by Gordon Moore). That idea—that technology would get smaller, faster, cheaper, and more powerful year after year—along with the breakthroughs in space technology and nuclear and atomic science, led to a techno-optimism that was part of the zeitgeist of the early 1960s. It also followed two decades of rapidly rising home ownership and steady rises in the adoption of household appliances, like refrigerators, air conditioners, washing machines, and vacuum cleaners—and of course personal automobiles.

Science was cool, technology was blossoming, and more and more Americans were dreaming of owning their own homes, replete with the latest gadgets. The Jetsons took that dream and supercharged it, riding the wave of optimism to depict a future where technology catered to our every need, at the touch of a button or at the command of our voice. It was a fantastical vision that deeply appealed to our needs and desires for comfort and convenience. Life on The Jetsons was anything but hard. Jetsons World was also clean, even antiseptic. In hindsight it’s easier to see what’s missing (besides people of color). Nature, for example, was not entirely absent, but it only makes a few cameos (some occasional greenery popping up on a floating office complex; a “park” where Elroy, the young boy in the family, plays with Astro, appears in one episode). It’s as if, in a future where technology reigns, we don’t need it anymore. Food (it’s not clear where it comes from) is at best efficient and seemingly never enjoyed. (Of course, Judy, the teenage daughter, is on a diet.)

Whether The Jetsons was a blueprint for the future or simply a prediction of it, it foreshadowed many of the products and services we now use today. It gave us self-driving, robotic vacuum cleaners; computers you can talk to with natural language; robots that play with children; and personal video conferencing. (It even recognized that people would be concerned about how they look on video calls, so it had masks you could put on to cover your morning face—anticipating the filters we use in Zoom, Snapchat, and elsewhere). It featured a sealed tube transportation system, a la Hyperloop; a remote, video-based group exercise class along the lines of Peloton; and doctors that make remote house calls via video screens. Naturally, The Jetsons used pocket-sized, wireless communications devices. Newspapers, embedded with videos, appeared on large screens, anticipating contemporary online editions of the New York Times and all other major newspapers. It had flying video cameras that followed you around and filmed you, as we now get with lightweight personal drones. You ordered food by tapping menus on a screen, as we sometimes do now, especially at airports. And of course, giant flat screen televisions were everywhere—just as they are now—and even the home theater, a room dedicated to viewing a large screen, makes an appearance.

It also gave us visions that we haven’t yet achieved, some of which remain targets of innovation. There were flying cars, which we don’t have yet, but be patient—there’s a nascent industry of companies with functioning prototypes and generous financial backing. (One of the leading companies is literally named Jetson.) There were moving sidewalks, dubbed “slidewalks,” to connect buildings and, within offices and even the Jetsons’ own apartment, chairs that automatically slid across the floor from one room to another. There were anthropomorphic robots, serving as butlers and maids. (They’re not commercially available today, but Elon Musk has promised them.) And beyond the humanoid robots, The Jetsons featured a bevy of robotic devices that cooked dinner and set the table, washed and ironed their clothes, styled their hair, shaved their faces, dressed them, and even gave them martinis at the ends of their “hard days” at work. And if the flying cars and the slidewalks weren’t enough, Jetsons World had jet packs, anti-gravity belts, and even a prototype of the thought-controlled flying suit that Tony Stark made famous in Iron Man.

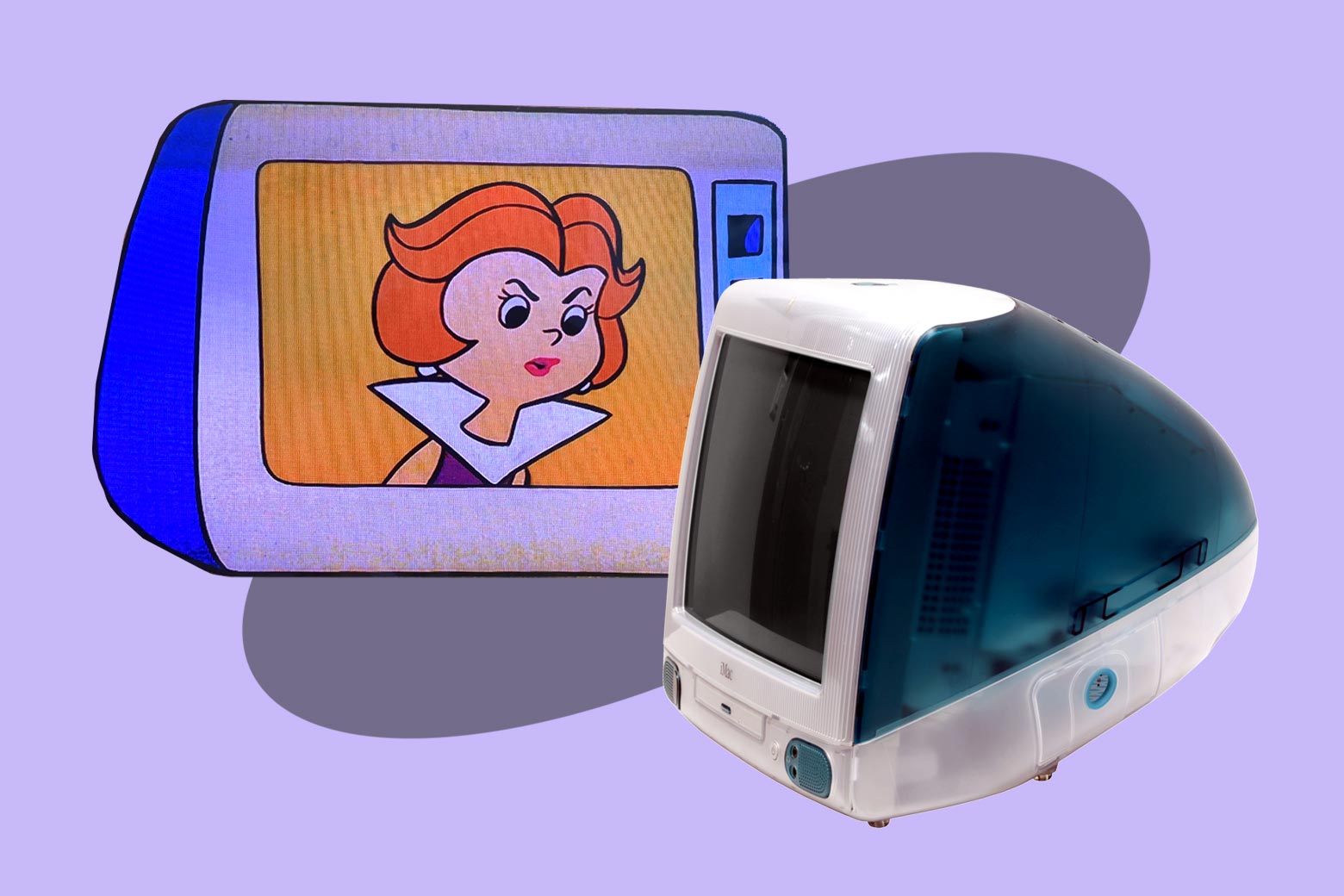

In some cases The Jetsons did work as a blueprint. When Steve Jobs returned as Apple CEO in the late 1990s, he pushed his design team, led by Jony Ive, to break the mold of the beige, square personal computer designs of the time.* Ive reputedly asked his team “What computer would The Jetsons have had?” The answer wasn’t hard to find in the cartoons, and this model, used by Jane Jetson to talk with her husband, George, looks eerily similar to the first iMac.

The cultural influence of The Jetsons continues beyond the retro-cool direction taken by Jobs and Ive. Sometimes it takes the form of references to literal artifacts and other times, more subtly, the influence is seen in the adoption of the fundamental motif of convenience that was emblematic of life in Jetsons World. Silicon Valley investor Peter Thiel famously lamented in 2013 that “we wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters,” invoking Twitter as the poster child for the kind of tech innovation that didn’t bring real value to everyday life. Dara Khosrowshahi, the CEO of Uber, a company that was once described as “a remote control for the real world,” spoke about his vision in a 2021 interview: “Right now, I dream about pushing a button and getting a piano delivered to your home in an hour and a half.” Elon Musk, in introducing the “Tesla Bot,” the forthcoming humanoid robot, said, as he often does, the quiet part out loud: “in the future, physical work will be a choice.”

Khosrowshahi, who explained that we should be able to use Uber to get anything we want, taps into the real zeitgeist of The Jetsons—the push-button convenience that our technology enables. All the complexity of procuring something, whether a piano, a pizza, or a ride across town, is abstracted away and reduced only to the question of which button to push, which part of the screen to tap, or which command to bark at Siri, Alexa, or Google. The convenience that The Jetsons presaged is now all around us, from TV remotes to Roombas, from Alexa to Uber, from DoorDash to Amazon Dash Smart Shelf, which automatically orders new goods when it senses they are running low. The convenience reflects both the savings of time, creating more leisure, and the reduction of physical effort, as Musk noted. One could even argue, taking Musk’s prediction to its logical conclusion, that the amount of physical effort needed to live day to day is asymptotically moving towards zero. Consider lawnmowers, for example: We have moved from manual mowers that we pushed around our lawns, to power mowers we followed around the lawn as they pulled us, to ride-on mowers (which saved our legs but at least required some arm movement to steer), to the latest, satellite-guided robotic mowers that cut the grass without engaging our bodies in any way whatsoever. As our technology grows ever more brilliant, our bodies grow superfluous.

Did The Jetsons inspire generation of innovators to realize both the many artifacts and the essence of its vision? Or did the writers understand the core human needs for comfort and convenience, and by extrapolating from the emerging technologies of the time, brilliantly imagined a future that was effectively predestined in any market-driven society? Both explanations are likely true to some extent, but whatever the reason, we have pursued—and partially achieved—the future The Jetsons depicted. And we continue to pursue it, applying a bursting pipeline of new technologies in the service of greater convenience.

The writers of The Jetsons gently mocked this culture of convenience. The scripts are peppered with ironic comments about working too hard, in relation to housework, for example, which consisted of pushing the requisite buttons. George needs to relax at the end of his “hard day” at work, which consisted of sitting back in a chair with his hands clasped behind his head, peering at a wall of controls and occasionally pressing a button or fiddling with a knob. And Jane needs to take an exercise class, where she works out her fingers, to make them stronger for all the button pushing she needs to do.

While The Jetsons might have made fun of the easy lifestyles that the technological future would produce, it completely missed the impact on the humans who would live in that future. It did not speculate about what would become of our bodies if we were to eliminate physical movement from our days; if we were to abandon cooking and feed ourselves with food prepared by machines; if we were to forego nature and deprive ourselves of its sights, sounds and smells. There was no recognition, no anticipation of the consequences to our health. In fact, nearly all the characters in The Jetsons are (cartoonishly) skinny. One episode casually notes that life expectancy is 150 years. There’s even an episode featuring George’s 110-year-old and absurdly spry grandfather, Montague, who plays ball with Elroy, drives like a joyriding teenager, and dances on the ceiling. Montague notwithstanding, the health of the characters on The Jetsons largely mirrored the times and didn’t foreshadow what might come from the dramatic changes in lifestyles, if followed to their logical conclusions. That task would be left to another cartoon: Pixar’s 2008 animated film Wall-E, in which morbidly bloated humans were shuttled around on reclined “hoverchairs,” with built-in screens and with sodas available on demand, delivered by drones (a sort of aerial refueling, perhaps). In this world, humans had become so physically dependent on their technology that, once fallen, they literally could not get up.

In the 60 years since The Jetsons aired, we’ve seen dramatic rises in the sort of “lifestyle diseases” that result from the culture that the series envisioned. More than 42 percent of American adults now live with obesity—a tripling since 1962—and another 30 percent are overweight. Severe obesity, which barely registered in the 1960s, now afflicts 9 percent of Americans. Diabetes has grown more than tenfold, now reaching 11 percent of the adult population. And the numbers keep rising. We have, in the view of evolutionary biologist Daniel Lieberman, created a world for which humans are not well-suited. And we continue to build it with little to no regard for that mismatch. We are proceeding in a manner that is unsustainable: We apply each new generation of technology in ways that guide us away from the day-to-day behaviors our bodies and minds need to flourish. Thankfully, dinner doesn’t yet come from a Food-O-Matic, but pizza robots are already a thing and cooking at home has been in decline for decades. Self-driving cars now seem perpetually a few years away, but what happens when they do arrive en masse? One study showed that people will likely increase their miles driven by up to 60 percent. And while there might be some buzz today about e-bikes and cargo bikes, they will likely be no match for autonomous vehicles that will promise unlimited entertainment or even the ability to sleep through your commute, as Ford’s CEO Jim Farley has promised.

At the end of each episode of The Jetsons, George takes Astro for a “walk” on a treadmill cantilevered off of their apartment. A cat momentarily jumps on the treadmill, spooking Astro and sending George tumbling. George is then stuck to the treadmill, going around and around, unable to stand up and unable to let go, screaming “stop this crazy thing!” The Jetsons’ treadmill serves as a metaphor for our current predicament. We generate new technologies, which we use to create new products and services, which lead us to unhealthy lifestyles that make us ill, then we create products and services like treadmills and FitBits to try to compensate for these lifestyles and new medicines to make the resulting illnesses tolerable. And then more technologies, products and services that make our lifestyles even less healthy and then around the cycle, again and again. And like poor George, we find it hard to extract ourselves from this cycle. Our economy demands growth and each element of the cycle—the new products, the compensating products, and the medicine—feeds that growth.

It will be challenging to escape, but if we do remain trapped in this cycle we will, as a population, get sicker. In the spirit of The Jetsons, we will of course continue to develop techno fixes, such as more medications that control the worst consequences of lifestyle-induced diseases. (Some side effects might occur.) We will continue to build tools to help people overcome the world we are creating. Perhaps high-end self-driving cars will come equipped with Pelotons so we can compensate for lost activity. But it won’t be the same as walking down a tree-lined street on a sunny day. Delivery bots might bring us nutritionally fortified pizzas made by robotic kitchens. But they won’t taste as good as a home-cooked meal from a family recipe nor will they come with the ambiance of the friendly corner restaurant. We might be able to chat with the avatars of long-lost friends in the Metaverse, but we won’t feel the warmth of their hugs. We can continue to build Jetsons World. And it’s tempting, because it looks pretty cool. But it doesn’t work so well for human beings.

One can argue that in 1962, when The Jetsons warmed our parents’ and grandparents’ living rooms and seeded their dreams with optimistic visions of a technologically-driven future, we didn’t understand the consequences to our bodies and our minds. But now we do. We now know that if we create products and services that result in people leading largely sedentary, indoor lives, with insufficient sleep, increasing isolation and diets based on large quantities of convenient, ultra-processed foods, we will suffer. Now that we know this, we need to act differently. We need to harness new technologies to lead us into healthier lifestyles—by design—and not as an afterthought. Summoning the will and creating the cultural momentum for the adoption of such an intention will require inspirational visions of the future that can succeed the vision imprinted upon us by The Jetsons.

It will be harder today to showcase new visions with the broad cultural footprint that The Jetsons could create in the 1960s, when a cartoon could expose an entire generation through Saturday morning reruns. One can more easily imagine an aesthetic that pervades many depictions of the future in popular culture—to the point that people internalize an expected direction for the future. Just as the techno-optimism and homogeneity of Jetsons World revealed the cultural biases of the time, the diversity and potential inclusiveness of a broad range of visions that share a general aesthetic and that are powered by a core set of values could reflect the more developed understanding of both pluralism and the tensions that arise when we impose new technologies on society. Insofar as we need visions that are compatible with what we know humans need to flourish, we will need to imbue them with a healthy respect for what we have learned from evolutionary biology and from the wisdom of indigenous peoples and our ancestors who managed to live sustainably for a lot longer than we have in the industrial and information ages. We will need visions of the future that connect us to nature—rather than set us apart from it. Visions that elevate the nutritional, social and experiential roles that food can play in our lives. Visions that recognize the deeply human need to connect with one another rather than to seek isolation. Visions that balance our bodies’ need to rest with their need to move—and in which those with physical limitations can count on any level of capability they choose. And ultimately, visions in which technology can facilitate these reconnections with the behaviors and experiences for which natural selection has optimized us—rather than alienate us from them.

The writers of The Jetsons might have missed the impact of their envisioned world on people’s health, but they clearly had some misgivings about the space-age future they animated. Through their occasional insertion of machine malfunctions and, most viscerally, when they trapped poor George on the treadmill, they warned us. Sixty years of pursuing their vision has brought us, as Paul Simon once put it, the age of miracles and wonder. And yet those warnings also ring true. We’ve now learned enough to know that this pursuit comes with unsustainable consequences. We’re now equipped with a more sophisticated understanding of the complex interplay among humans, technology, and the Earth. Let’s use that understanding to chart a new course.

Correction, Sept. 23, 2022: This article originally misspelled Jony Ive’s first name.

Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society.