Broadcasters Make Big 3.0 Bet At NAB

L-r: Anne Schelle, the Pearl Group; John Hane, Spectrum Co.; Mike Bergman, Consumer Technology Association; Gordon Smith, NAB; and FCC Commissioner Brendan Carr (at podium).

LAS VEGAS — After several years of mostly behind-the-scenes work on the ATSC 3.0 next-generation standard, the country’s biggest broadcasters finally showed their hands in a very public way at the NAB Show in Las Vegas this week by committing to launch ATSC 3.0 on stations in the top 40 markets by the end of 2020 — the same time 3.0 TV sets should be hitting retail shelves in meaningful volume.

The announcement was significant in not just its scope but in the cooperation it required between two groups who have often expressed differing views of the 3.0 future: Spectrum Co., the joint venture founded by Sinclair and Nexstar to roll out the new standard; and Pearl TV, a consortium of eight major groups including Cox, E.W. Scripps, Graham Media, Gray, Hearst, Meredith, Tegna and Nexstar.

It also brought aboard major players who aren’t part of either consortium, in the form of both the Fox- and NBCU-owned stations as well as Univision, Capitol Broadcasting, Hubbard Broadcasting, News-Press & Gazette, APTS and other public broadcasters.

“This is a landmark development in the transition to a new digital standard,” says Pearl TV Managing Director Anne Schelle. “This moment should not be unrecognized.”

Which is true. But as with many bold new initiatives, the devil’s in the details — and besides a list of markets, there were few to be had, such as station call letters or market launch schedules. Almost every executive involved with the process says that has less to do with technology and more to do with legal agreements and business negotiations — in particular the arrangements by which ATSC 1.0 stations in each market will channel-share, or “stack” existing services, in order to free up at least one station to launch 3.0 services.

Participating affiliates also have to reach agreements with their respective networks over how programming will be handled, and also get verbal consent from syndication partners to their plans.

For now, stations also have to apply to the FCC for experimental licenses, or STAs, to launch 3.0 since the FCC does not yet have an official application form available; one might be available in May. Given the number of STA applications for ATSC 1.0 the FCC is expected to field as part of the ongoing RF repack process, it could be a very busy spring at the commission.

Spectrum Co. President John Hane says that the cooperating groups have, in fact, identified the first 60 markets, and that planning for those additional 20 is already underway. Sinclair has 26 markets it can do, and with Spectrum Co. that brings the total to 32.

“The first wave we have more control, but it’s an aggressive timeframe, and we have some big markets that are more complicated,” says Hane. “There are markets that are more and less complicated. If you’re seeing some markets launched more quickly than others, it’s not because we prioritized them — it’s because they were less complicated and got done faster.”

He adds that the first big hurdle to the launch has already been cleared, which is proving to broadcasters that new MPEG-2 compression technology is good enough to squeeze the ATSC 1.0 programming displaced by 3.0 launches onto other stations’ channels without noticeably lowering their picture quality. In a suite at the Wynn hotel here, Spectrum Co. executives were running side-by-side demonstrations of various prerecorded ATSC 1.0 feeds on two HD displays.

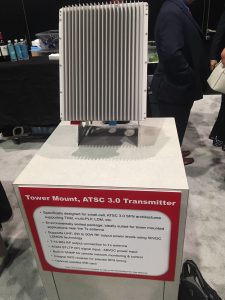

A compact, low-powered Hitachi-Comark transmitter designed for “dense SFN” applications. (Glen Dickson photo)

One demo had a statistical multiplex of one 720p HD feed and 3 SD diginets, compressed by a legacy Harmonic hardware-based encoder, compared to a statmux of one 720p HD feed and 6 SDs, compressed by Ateme’s latest software-based encoder. The second demo showed 1 HD and 3 SD streams using the older encoder versus 2 HDs and 4 SD streams using the new encoder.

Broadcasters were asked if they could pick which HD picture was which, and according to Spectrum Co. COO Sasha Javid, most couldn’t see any difference (to his point, this reporter saw the first demo and incorrectly picked the statmux run through the Ateme encoder as being the one with the lighter, not heavier, payload).

“The [incentive] auction paved the way to a certain extent with channel-sharing arrangements, but people are concerned about what that does to the picture quality,” says Javid. “People want to see it with their own eyes. So we’re inviting them to come down and take the eye test, to see if they can tell the difference. New encoders have come a long way, and numerous brands support this kind of stacking.”

Deployment Decisions

While broadcasters seem to have found consensus on how to get 3.0 signals on-air, their long-term plans for business models are still unclear. Part of that is a function of just how much technical flexibility the 3.0 standard affords, including the ability to transmit up to four PLPs (Physical Layer Pipes) with dramatically different data payloads and reception characteristics. By altering the modulation and error correction coding, or “mod/cod,” settings of the PLP, the effective payload can range from 0.8 Mbps up to 57 Mbps in a 6 MHz channel.

“ATSC 3.0 is a toolbox with a lot of different tools,” says Joe Turbolski, Hitachi-Comark VP of sales and marketing. “But nothing is free — throughput will cost you range.”

Comark’s booth demonstration of an end-to-end 3.0 system gives one a quick education. It showed six simultaneous 1080i HD feeds being sent in a single PLP, with 256-QAM modulation and coding set for less robust reception that delivered an effective payload of around 27 Mbps. Such a configuration might be ideal for delivering HD to living-room sets.

Harmonic was using a Sony smart TV to demonstrate how broadcast and broadband pipes can work together in ATSC 3.0. Faster channel change times are one potential benefit. (Glen Dickson photo)

Playing around with the Enensys Broadcast Gateway user interface allowed one to quickly create a very different PLP, with QPSK modulation and coding set for very robust reception and an effective payload of just over 1 Mbps, which would probably be used only for mobile reception in the most challenging environments.

“You can pull that out of the weeds,” says Turbolski.

That range of options gives some pause to TV set manufacturers, who in the near term would like to see broadcasters agree on a common go-to-market message that preferably includes better-quality pictures for the living room. If broadcasters don’t deliver true 4K UHD, then 1080p/60 HD with High Dynamic Range (HDR), a format many broadcasters have expressed interest in, would be an easy message to market, says Matt Durgin, senior director of content innovation for LG Electronics.

But whatever it is, consistency is key.

“It would be extremely ineffective if our vision on what consumers are going to get excited about with ATSC 3.0 and our marketing dollars go toward one aspect of the technology, and then, we didn’t know at the time, that somebody else was out there with a completely different message,” says Durgin. “You’d think that would be a good thing, but in actuality, that tends to generate some customer confusion. So it would be great for us to see industry groups getting everybody into one place and putting together some thoughts about what is ATSC 3.0’s priority list in terms of how we go and market that.”

Schelle says that broadcasters are already working with CTA on a certification process for 3.0 sets and an accompanying logo that could be displayed at retail to help clarify 3.0’s benefits for consumers.

One thing that is clear from speaking with broadcasters this week is that if they do deliver 4K, at least some, if not all of it, will be delivered via 3.0’s broadband pipe as they would like to conserve their 3.0 bandwidth to launch other services. And what route (or ROUTE, as in Real-time Object Delivery over Unidirectional Transport) they take is one of the big technical decisions facing the industry.

Some broadcasters advocate an approach called scalable HEVC (SHVC), whereby a 4 or 5 Mbps 1080p/60 HD signal would be delivered over the air and a roughly 10 Mbps “enhancement layer” would be sent via the broadband pipe, with the two being combined at the 3.0 set to display 4K. This approach, which was being demonstrated in the Korean research organization ETRI’s booth, uses different streaming protocols for the OTA and OTT parts of the signal including the MMT (Media Processing Unit/MPEG Media Transport) protocol on the broadcast side, which isn’t yet adopted by U.S. smart TVs.

Another approach, which Harmonic has been testing with Weigel Broadcasting in Chicago, is to use the established DASH (Dynamic Adaptive Streaming over HTTP) protocol in both the broadcast and broadband streams, but to deliver the UHD solely in the OTT pipe.

This approach requires more bandwidth over broadband — the 4K UHD would require 14 to 15 Mbps. But it would allow broadcasters to take advantage of an existing DASH ecosystem that already includes a number of smart TV sets — including 3.0 backers Sony, Samsung and LG — as well as all existing Android smartphones. That would let broadcasters leverage existing DRM and dynamic ad insertion tools that are already used broadly today.

“That becomes possible when you latch onto the DASH OTT ecosystem,” says Harmonic’s Jean Macher, director of broadcast market development. “We shouldn’t, as an industry, try to fix the Internet. The Internet doesn’t need ATSC 3.0. What we should do is try to catch up.”

Dense Vs. Sparse

While Spectrum Co. is currently operating a single-frequency network (SFN) in Dallas and Pearl is in the process of developing one in its Phoenix Model Market, the initial top-40 market plan doesn’t feature SFNs.

“The plan is to get it launched in as many places as possible,” says Hane. “Get the population covered, and then you can optimize later … for every broadcaster, the plan is to get content launched.”

But long term there will likely be some tough decisions for broadcasters to make about what kind of SFN they build out. The SFN in Dallas and the one Pearl is building in Phoenix are both based on the “sparse” SFN model, where a traditional “big stick” tall tower with a high-powered transmitter is complemented by three to four lower-powered transmitters feeding antennas on small-to-medium size towers.

Another approach is the “dense” SFN model, where a broadcaster would place dozens of compact, low-power 3.0 transmitters throughout a market, probably on conventional cellular towers, in order to aggressively deliver mobile video and data services, particularly to vehicles.

Prototype home gateways at the ETRI booth with ATSC 1.0, ATSC 3.0 and OTT capability. (Glen Dickson photo)

In fact, Mark Aitken, Sinclair VP of advanced technology, has been pitching the dense SFN as part of a “5G broadcast” solution where very low-power 3.0 transmitters would be co-located alongside 5G transmitters and take over the data load from the 5G network during high-volume streaming events like live sports. Besides robust reception, an advantage of this approach is that it would take advantage of a tower and fiber connection infrastructure that has already been developed by wireless carriers.

The relative merits of such a scheme depend on where one stands. Akamai, the leading content delivery network (CDN) which already does a lot of 4G streaming worldwide, doesn’t see the point. Akamai Chief Architect Will Law says that it has already delivered 11 million concurrent streams for professional cricket matches in India, with 93% of them going to mobile phones through the cellular network.

“You can do multicast through a 4G and a 5G network,” says Law. “We’re doing a trial in India on multicasting precisely to solve the peak capacity problem. So rather than deploy additional ATSC 3.0 boxes on towers, you just reuse the existing cellular network and you create your multicast stream.”

ETRI principal researcher Dr. Sung-Ik Park with an ATSC 3.0 tablet tuner dongle. (Glen Dickson photo)

On the other hand, Crown Castle, which owns 40,000 towers and 65,000 miles of route fiber with the lion’s share used by wireless carriers, sees the convergence of 5G and 3.0 as a more plausible opportunity. Jeff Baker, VP of business development for Crown Castle, says he is excited by ATSC 3.0’s “big data pipe.”

He points out that wireless carriers already look at multiple buckets of spectrum, aggregate spectrum and combine different frequency bands to secure better coverage, in addition to doing Wi-Fi offloading. With video streaming over cellular networks increasing rapidly, he thinks it’s inevitable that carriers will take advantage of 3.0 as a 5G offload.

“I think where you end up eventually, is that broadcasters have networks that look very much like traditional wireless networks,” Baker says.

Whatever long-term decisions broadcasters might make about broadband delivery protocols and SFN architectures, they best make haste in getting 3.0 rolled out, says Sinclair Broadcast Group Executive Chairman David Smith. Smith, who along with other Sinclair executives has been advocating for a broadcast DTV standard capable of reliable mobile reception for over two decades, says the NAB launch announcement is “simply the end of the beginning” in creating a new data delivery platform for broadcasters.

“When you think about what’s ahead of us here, there’s clearly going to be a lot of friction involved in trying to get this activity executed — friction not the least of which will be driven by people who don’t want us to be successful,” Smith says. “So it’s incumbent on us as an industry to literally coalesce behind, market by market by market, and get this thing built out for the express purpose of the broadcast industry surviving.

“Nobody 10 or 15 years ago would have thought that the thing that really drives the growth today isn’t pictures and sound as much as it is data,” Smith adds. “And there are a lot of folks in our industry who don’t think we’re really in the data business. I would tell you that data will probably be the sole opportunity that keeps us afloat for the next generation.”

For more NAB Show coverage, click here.

Comments (0)