TVN Tech | Camera Robotics Get COVID Proving Ground

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated broadcaster use of robotics for remote operations of cameras, and the capabilities of these tools continue to increase.

4K lenses deliver sharpness. Internet protocol-based cameras helped prove the bandwidth exists for broadcasters to transmit video over IP. Control of camera movement has both quieted and improved to provide smoother starts and stops.

And the robotics that move the cameras have become increasingly sophisticated, allowing better face and object tracking as well as features like new movement patterns and repeatability. Vendors say future products will feature improved automation.

“COVID-19 changed our lives. Regardless of the industry, it changed the way we work,” says Eisuke “Ace” Sakai, B2B business manager for Sony Electronics.

Shotoku Managing Director James Eddershaw says people have found methods such as software panels to overcome the “real headache” of operating systems remotely from home offices.

Grass Valley’s LDX 100 camera series offers native IP connectivity, allowing the camera to be integrated directly into IP infrastructures for both local and remote workflows.

And sports are one area where the use of camera robotics have really expanded, says Bruce Takasaki, product manager for Camera Motion Systems at Ross Video. Traditionally, he says, robotics in sports have been largely limited to remote cameras where a person wouldn’t be stationed, such as by a goal post or a net in hockey. COVID social distancing requirements, however, have meant fewer people in sporting facilities.

“We started seeing interest in robotics for the main cameras, not just the extra cameras,” Takasaki says.

Thomas Fletcher, director of marketing for Fujifilm, says the pandemic has led to the company delivering bigger lenses for pan and tilt cameras.

He also says broadcasters looking to futureproof their lens purchases are often opting for 4K lenses over HD lenses. The 4K lenses use “better pieces of glass” and improved coatings to achieve higher resolution and provide the ability to “make a nice HDR image,” he says.

“Some people are not buying the lenses first and foremost because of the 4K resolution, the sharper lens. They’re buying it because it’s making a more dynamic picture as HDR is on the horizon,” Fletcher says.

Looking to the future, he says, broadcasters want their lenses to be able to focus in real time, avoiding the lag of the lens sending a signal to the camera operator.

“Autofocus is the next thing they’re looking for,” Fletcher says. And that technology, he says, is “just getting faster, more reliable and more functional.”

IP-Based Cameras Gain Currency

COVID has “changed the whole discussion” around IP-based cameras, says Ronny van Geel, director of product management at Grass Valley. “At first, it was: ‘It will never happen.’ Then it was: ‘There will never be enough bandwidth to enable this.’ What the pandemic has done is it has proven to everybody who was a skeptic that the bandwidth is there, and this can work.”

In short, he says, the conversation has shifted from why a broadcaster might want an IP-based camera to how the broadcaster can use the technology and what lessons have been learned in the field to date.

“Now there are many more unmanned camera positions … that are now controlled remotely by pan-tilt robotics,” van Geel says.

The Associated Press covered the first 2020 Presidential debate in Ohio from above with a remotely-controlled Telemetrics DSLR camera rig.

Grass Valley’s LDX 100 camera platform can send a “mind-blowing” amount of signals to the field and pick up the streams it needs, van Geel says. That camera was introduced last year, and later this year, says Bart Van Dijk, product manager at Grass Valley, a compact version of the LDX 100 will go on the market.

Drew Buttress, B2B senior product manager for Sony Electronics, says one of Sony’s recent firmware releases for its high-end PTZ cameras can slow the motor down to a fraction of a degree per second.

“You as viewer wouldn’t see the start of the zoom, but you’d noticed we’re creeping in or out from person’s face,” Buttress says.

In addition to smooth and controlled movements, broadcasters also want the ability to repeat a shot, he says. Sony offers a pan-tilt-zoom (PTZ) trace capability that can save up to three minutes of a live move, and a few broadcasters are using that solution, he says.

Select Sony PTZ cameras support the Free-D protocol allowing productions to easily incorporate VR/AR into their live content, such as expanded sets or scenery, live animations, e-sports and graphic overlays.

Jim Jensen, senior business development manager for Panasonic System Communications Company of North America, says the PTZ cameras now on the market are far more advanced than those of years past. New models are capable of streaming and making remote production operations easier, he says.

Last year, Panasonic introduced its AW-UE100 PTZ camera. Its direct drive motor makes it “extremely quiet and quick,” Jensen says. “Because of the PTZ success, there’s been a higher demand for more production value, and that’s where the robotics come in.”

Robotic Precision

Paddy Taylor, head of broadcast for Mark Roberts Motion Control, says one of the draws for robotics is their precision. “Robotics will always go back to the exact same position, reliably. Humans will get it pretty close, but not exactly,” Taylor says.

ABC Arizona uses one of MRMC’s robotic arms systems to create reliable signature moves for its broadcasts, he says.

MRMC’s Polymotion Chat is an automated subject tracking solution that can control up to six camera positions. Here it’s seen in a studio with a broadcast camera and a PTZ camera.

Another solution, Polymotion Chat, is an automated tracking system that tracks 18 pivot points of the talent, Taylor says. As such, it takes facial tracking to the next level, he says.

“Polymotion Chat found an audience due to COVID,” he says. “Suddenly, engineering managers that wouldn’t consider it are now embracing it.” It is “providing the heavy lifting” to help broadcasters do more with less, he says.

Minimizing In-Studio Personnel

Robotics can help minimize the number of people needed in the studio.

One major sports broadcaster is using equipment like panbar systems to keep camera operators out of the studio, Takasaki says.

“They just wanted to have the natural feel their operators were used to,” he says. “It’s a situation where they weren’t using robotics before.”

And software is what drives the robotics. “We are focused on adding more smarts to our robots so they can do things more effectively with less interaction,” Takasaki says.

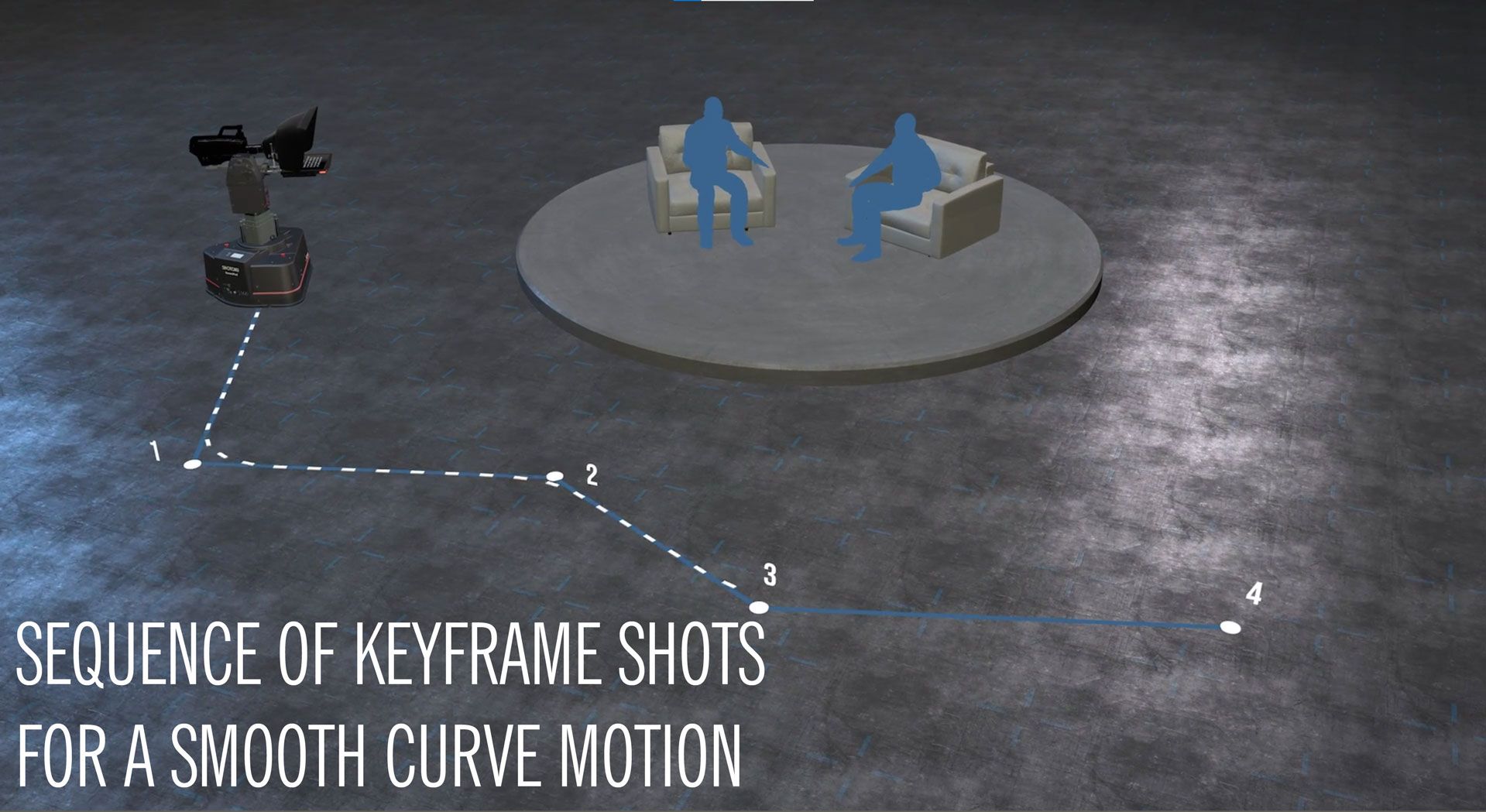

Ross Video’s MotionDirector software, introduced for the Furio dolly in 2019, can now control CamBot XY pedestal movements, Takasaki says. Now, the CamBots can do key-framed moves on the floor along curved paths around the studio, and movements can be replayed.

One of the fundamental needs of a robotic system is the ability to have freedom of movement, Shotoku’s Eddershaw says, and the easier that is, the better. Once, it was enough just to move from point a to point b in a straight line. Now, it’s possible to send a robotic pedestal “in a more interesting pattern” with smoothed-out motion, he says.

Shotoku’s Sequence allows operators to complete complex curve motions by seamlessly moving through a series of key frames.

“Broadcasters want to be able to produce more interesting shots, and that almost always involves movement,” Eddershaw says.

During the second quarter, Shotoku plans to release Orbit Mode, which will allow a robotic pedestal to move in an arc, either clockwise or counterclockwise, he says.

Shotoku has already launched its AutoFrame product, which can identify faces, lock onto the face and smoothly pan to keep framing the presenter as the talent moves, he says. “Face tracking is a big thing,” he says. “It will just get bigger and bigger with AutoFrame,” which integrates into the TR-XT Control System.

Part of what Telemetrics is working on is visual and object tracking, says Michael Cuomo, the company’s vice president. In short, he says, the company is working to bring more AI into the robotics’ control system. The company is also working to bring robotic cameras into types of programs where they haven’t historically been used, such as non-scripted shows, Cuomo says.

“The goal is to have multiple cameras be operated by one person in a non-scripted environment,” Cuomo says. “We need to convince customers that it’s possible. We’re starting to get to that point.”

In the last six months, he says, customers have begun to accept the technology and indicate a willingness to try it. Even if all cameras on a program can’t be operated by a single person, it’s possible to see a reduction in operating costs by moving to robotics, he says.

IP equipment has been a key part of making the shift to remote operations possible, says Neil Gardner, Vinten product manager.

This set from Better Together on TBN uses two Panasonic AW-UE150 4K 60p integrated pan/tilt/zoom cameras.

The last decade has seen a lot of progress toward IP equipment, Gardner says, and the last year has seen a major change in specifications that allow full remote access into studio equipment like cameras and the robotics that move them.

Challenges include latency concerns, video feed back into the home environment and providing remote equipment interfaces that still have the same feel that people are used to from the control room, he says.

Machine Learning, Voice Control

The future for cameras and robotics, Gardner says, is “all about further automation through an understanding of the video that’s being played by the system.”

One area that could see some technological advances is voice control of robotics, which would make it possible for a non-specialist to make adjustments, he says. Current challenges are the need to understand different phrasings for commands and colloquialisms, he says.

Machine learning with regard to studio robotics is also a hot R&D topic, he says. Currently, it’s not possible to fully automate certain systems because manual operators pick up many cues that robotics aren’t programmed for, he says.

“A camera operator tracking someone walking will from their body language get a cue as to when they’re going to change direction or stop walking,” Gardner says. “The control system needs to be able to do that.”

The challenge? Making it feel natural, he says. “Until those problems are solved, you can’t expect to see an automated control system start to replace what a manual operator does.”

Comments (1)

CvG says:

May 6, 2021 at 2:21 pm

At Seervision we have been doing intelligent tracking based on computer vision and machine learning for 5 years. Our software is also hardware agnostic, so not tied to any specific manufacturer. In addition, we enable automation processes that make a completely autonomous operation of a multi-camera setup possible, come check us out at seervision.com