When the closing gavels came down on the 2016 political conventions, the news cycle did not ease into the usual midsummer lull but instead locked directly into a state of high alarm, with Donald J. Trump at its center. In the days following Trump’s nomination, there came reports of senior Republican officials considering ways to replace him on the ballot (ABC News), of “suicidal” despair inside the Trump campaign (CNBC), and of a growing list of Republican leaders who planned to publicly support Hillary Clinton (Time). Fox News reported that friends of Trump’s were planning to stage an intervention, involving his family, in hopes of saving his candidacy.

But amid those passing controversies was one story that Trump himself remembers clearly still. “Yep, very famous story,” he remarked to me in a recent interview. “It was a very important story...” Trump was referring to a front-page New York Times article published on August 8, 2016, under the headline "The Challenge Trump Poses to Objectivity." The opening paragraph posed a provocative question:

“If you’re a working journalist and you believe that Donald J. Trump is a demagogue playing to the nation’s worst racist and nationalistic tendencies, that he cozies up to anti-American dictators and that he would be dangerous with control of the United States nuclear codes, how the heck are you supposed to cover him?”

The author of the piece was Jim Rutenberg, an important byline at the Times. He writes a media column for the paper, a feature deeply informed by Rutenberg’s experience covering politics and as an investigative reporter. Rutenberg has a keen sense of current thinking in the media hive, and when he wrote that “everyone” was asking the questions he raised in his Trump “demagogue” column, it carried the weight of mainstream newsroom consensus. Reporters who considered Trump “potentially dangerous,” Rutenberg wrote, would inevitably move closer “to being oppositional” to him in their reporting—“by normal standards, untenable.” Normal standards, the column made clear, no longer applied.

Trump said that was an important article because “they basically admitted that they were frauds."

“They admitted in that story that they didn’t care about journalism anymore,” he continued, “that they were just going to write badly. That was an amazing admission.”

It’s an essential Trumpian assertion—wildly hyperbolic, but containing what much of Red America would consider a sort of rough truth.

The Rutenberg column was an astute and honest piece of analysis. The unavoidable takeaway from it was that Donald Trump, in shattering the norms of presidential politics, had baited the elite news media into abandoning the norms of traditional journalism—a central tenet of which was the posture of neutrality.

That certainly seemed to be the case at the Times, which soon began to characterize dubious Trump statements as “lies” in news reports and headlines, a drastic break from the paper’s once-indelible standards. For decades, Times journalists were deeply imbued with a sense of the Times’s way of doing things, instilled in them osmotically, as well as by consultation with the holy writ of proper form, The New York Times Manual of Style and Usage. The Style Book, as the manual was known in the newsroom (where I worked for three years in the 1980s), insisted upon a tone of impartial neutrality, the foundation upon which the Times’s claim to authority rested. Such common terms as “pro-life” and “pro-choice” were firmly rejected as being too politically charged. Tone was paramount. “Writers and editors should guard against word choices that undermine neutrality,” the 2015 version of the Style Book directed. “If one politician is firm or resolute, an opponent should not be rigid or dogmatic. If one country in a conflict has a leadership while the other has a regime, impartiality suffers."

This view of impartiality suffered mightily with the entry of Donald Trump into presidential politics, and the eventual decision to describe his inaccurate statements as “lies.”

Dean Baquet, the Times’s executive editor, told NPR that Trump’s falsehoods, such as his claim that Barack Obama wasn’t born in the U. S., were “different from the normal sort of obfuscations that politicians traffic in.” A “normal” political prevarication, Baquet explained, is “the politician who says, ‘My tax plan will save a billion dollars’ and when in his heart of hearts he knows it’s $1.9 billion that it’s not going to save; that, in fact, it’ll cost people.” As it happened, on the same day that the Times referred to Trump’s birther claim as a “lie,” it also employed the term in another story about Trump—on a subject that neatly fit Baquet’s definition of “usual political fare.” The Times reported that Trump’s campaign had made conflicting statements about the candidate’s proposal to offer huge tax cuts to small businesses. “Call it the trillion-dollar lie,” the paper declared.

It was the sort of editorial inconsistency that news organizations (excepting cable news’ more amped-up precincts) had once strenuously tried to avoid, bearing as it does on credibility and trust. Calling Trump a liar in news stories was a significant first step toward becoming openly oppositional, leaving readers little choice but to conclude that the Times would cover Trump as a “potentially dangerous” figure, as Rutenberg had termed it.

Even within the Times, there was at least one voice expressing concern about forsaking the old rules. Liz Spayd, who was the Times’s public editor in the early months of the Trump presidency, was the embodiment of traditional journalistic standards—a former managing editor of The Washington Post and the editor and publisher of the Columbia Journalism Review. We spoke at the time and she told me she found the turn toward oppositional journalism discomfiting. “I am a little worried, personally, about going too aggressively down that path,” she said, “or that being seen by reporters and editors at The New York Times as some kind of a gate that was just busted open, and now you can run through and do everything you need to do to take on this man.”

Jill Abramson, Dean Baquet’s predecessor at the Times, agreed with his decision to call Trump a liar but also recognized the risk that such departures from standards carried to the Times’s hard-earned reputation as the paper of record, so prized by generations of Times journalists. “Though Baquet said publicly that he didn’t want the Times to be the opposition party, his news pages were unmistakably anti-Trump,” Abramson wrote in her book Merchants of Truth, published in February. While she believed that the challenges of Trump’s campaign and presidency had pushed the Times to improve its journalism in many ways, the “more anti-Trump the Times was perceived to be, the more it was mistrusted for being biased.”

Where The New York Times led, others inevitably followed. The Washington Post, for instance, adopted the slogan “Democracy Dies in Darkness” a month into Trump’s presidency. Though the paper denied any partisan intent, the slogan landed as a clear poke at the president—if not a kind of Klaxons-blaring red alert. The risk for journalists is not only a loss of trust but also a loss of perspective, a predisposition to overhype the next item in a ceaseless cascade of “bombshells,” each promising to end the Trump presidency, many ending in a fizzle, or worse. The BuzzFeed story in January alleging that Trump had ordered his former attorney Michael Cohen to lie to Congress was feverishly seized upon by many in the mainstream news media, with only the faintly murmured caveat “if true.” The morning after the report, ABC Newsanchor George Stephanopoulos devoted more than five minutes of Good Morning America’s opening news segment to the BuzzFeed story. “Some Democrats on Capitol Hill are jumping on this report and calling for an immediate congressional investigation,” said the network’s Justice Department correspondent, Pierre Thomas. “And some potential presidential candidates are now using the I-word—impeachment.”

After the BuzzFeed story was shot down a day later by Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s office, there was a palpable sense of collective damage among the elite media. Jeffrey Toobin, a New Yorker writer and legal analyst for CNN and a consistently fierce Trump critic in both venues, conceded, “The larger message that a lot of people are going to take from this story is that the news media are a bunch of leftist liars who are dying to get the president, and they’re willing to lie to do it.” Speaking to a panel at Oxford University last year, Washington Post executive editor Martin Baron lamented that the news media seemed to be losing the power to influence events. “Journalism may not work as it did in the past,” Baron said. “Our work’s anticipated impact may not materialize.”

It’s almost as if the effort to undo Trump has had an unexpected effect—that Trump has somehow broken the news media.

It’s a proposition that Trump would not dispute. “Look, when I started, the news [profession] had a very high favorability rating,” he told me, referring to the launch of his political career, during a recent forty-minute phone conversation. “Now it’s down in the realms of...it’s as low as it can possibly get.” Some more Trumperbole, perhaps, but the news media’s bond of trust with its audience is certainly under strain. Is that your doing, I asked, or the media’s? “It’s my doing,” he said. “But it’s my doing with my good ammunition, my great ammunition.”

In light of the unprecedented disharmony that has characterized his relations with the news media, I asked Trump, “What, in your view, is the value to this country of a free and open press?”

“Oh, I think it’s important,” he said. “I think there are few things more important than a free press.”

He paused, and I was about to ask him why he’d disparaged the press as “scum,” “the lowest form of humanity,” “a stain on America,” and “the enemy of the American people” when he resumed answering my first question. “But see, I don’t consider fake news to be free press,” he said. “I consider that to be dishonest press.”

The term “fake news,” of course, has been part of Trump’s “great ammunition” in his battles with the press. He didn’t coin the term, but he has cannily made it his own and wielded it to great effect. A Monmouth University poll taken last year found that 77 percent of Americans believe that traditional news outlets report “fake news”—a significant leap from the year before.

I asked Trump whether he distinguished “fake news” from news that is unfavorable to Trump. “Well, fake news is news that’s made up,” he said. “I mean, fabricated. I’ll give you an example. I was in the office recently, in the Oval Office, with a group of businesspeople. And on the television, we were watching something where they were showing me. And they had a reporter out from CNN saying, ‘He’s upstairs in his suite at the White House brooding, and walking the halls.’ And here I am in the office, where I’m laughing with a very important group of traders, because we’re trying to get great trade deals for this country, and these were people who were working on that, and in two cases representing other countries, and we’re down there having a really good talk, and a very interesting one, and having a good time, actually, because we enjoyed what we did, and if you watched CNN, I was up walking the hallways, brooding. And they’re always doing that. They’re always saying, ‘He’s brooding, he’s angry,’ and I’m not! You know, I know how life goes. I get life better than a lot of people. I mean, I just get it. And I even understand where they’re coming from. But the problem is, it’s very dishonest, really dishonest.”

But through the course of our conversation, it became clear that Trump makes no meaningful distinction between, say, the disputed BuzzFeed story about Michael Cohen and news reports that are journalistically sound but negative to Trump. The vast majority of news reports in the Trump era fit into that latter category. He has claimed that 90 percent of coverage of him is negative, which may be another of his signature exaggerations. But a study by the nonpartisan Pew Research Center of press and TV coverage of Trump’s first sixty days in office found that 62 percent of stories about him were negative, compared with 20 percent for Barack Obama across his first sixty days and 28 percent for both George W. Bush and Bill Clinton.

Whether that discrepancy is due to bias or the uniquely tumultuous nature of Trump’s administration or some combination of the two will have to remain in the eye of the beholder. Trump seems genuinely bemused by his negative press. “I was surprised at some people that I’d always found to be fair, and all of a sudden they had a very different bent,” he said. This is owing, perhaps, to the fact that in his life before politics, Trump’s media profile was shaped largely by himself. In that New York version, Trump was the colorful, if slightly garish, operator whose lifestyle—the helicopters and planes, the hotels and casinos, the wives and girlfriends—was the tabloid ideal. His exploits sold papers, and the publicity helped make his name an indelible brand.

The fun stopped when Trump announced his run for the White House. He thinks it’s because he ran as a conservative Republican: “I used to get great press until I announced that I was gonna run...and the fact that you’re running as a Republican conservative, automatically, they put you behind the eight ball.” While it’s true that the news media are not known to be favorably inclined toward conservative policies, the negative reaction to Trump had more to do with the person of Trump—and especially his words, his aggressive hyperbole and verbal brushback pitches—than with policy prescriptions. Maggie Haberman’s writing about a colorful Queens real estate developer for the New York Post is going to be different in tone and substance from Maggie Haberman’s reporting about the president of the United States for The New York Times. That is particularly true if the president continues to talk and behave like a developer from Queens.

It is the local boy who anguishes over the tough coverage he’s received from the Times, his hometown paper. “I came from Jamaica, Queens, Jamaica Estates, and I became president of the United States,” Trump reminded Times publisher A. G. Sulzberger during a January sit-down in the Oval Office. “I’m sort of entitled to a great story—just one—from my newspaper.”

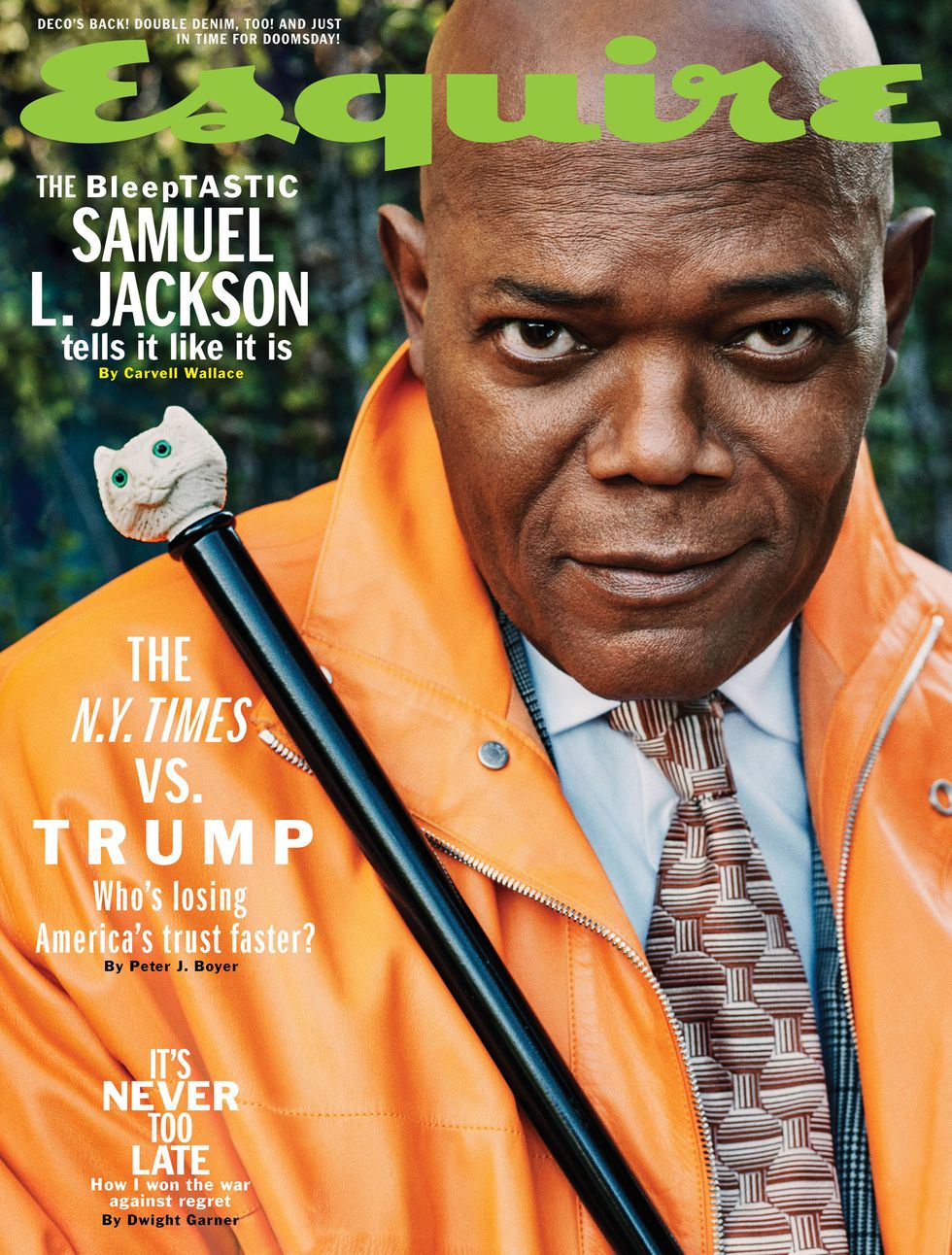

Want Esquire delivered on the daily? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Subscribe

Stephen K. Bannon, Trump’s former chief strategist, told me his old boss longs for the respectability conveyed by the Times—the one paper, Bannon said, that Trump reads every day, cover to cover. “He looked at me one time and he said, ‘You know, in all those years in New York, I had five page-one stories in the Times,’” Bannon recently recalled. “And he looked at the paper that day and there were literally five stories about him that day on the front page. And I said, ‘Here’s the problem—they all suck.’”

Bannon cited a day with Trump not long after the election when, he said, the Times was “just fucking hammering” the president-elect and protesters were gathering daily outside Trump Tower. “He says, ‘You know, I thought it would be different. Everybody would come together and say, Let’s work together and unify the country, and they’d kinda congratulate me that I won a hard-fought campaign.’ I said, ‘You’re kidding me, right?’ He said, ‘No, isn’t that what happens?’ He thinks he’s in a movie. It was so endearing.”

Since moving into the White House, Trump has added his new local paper to his list of irritants. “I’m trying to figure out which is worse,” he told me, “the Times or The Washington Post.” On the day we spoke, he was stewing over a story published in the Post a week earlier: “It was so inaccurate, it was incredible.”

Trump explained that he’d agreed to an interview with Post reporters Philip Rucker and Josh Dawsey “as an experiment” to test the Post’s fairness to him. Trump said he was on his best presidential behavior for the Oval Office session, and he thought the interview went well. “I did it just to see if I could, you know,” he said. “And I was on very perfect behavior. You’ve heard me say I could be the most presidential man ever, other than perhaps the late, great Abraham Lincoln—but only if he wears his top hat. I can be the most presidential of them. And I was more presidential [with the Post reporters] than anybody could be. And when you read the interview, it was disgraceful. It was a two on a scale of ten. And it should have been a very good interview. And I realized there is nothing we can do in The Washington Post or in The New York Times to be treated accurately. Not fairly. Accurately, not only fairly.”

The Post interview covered a range of subjects, from the policies of the Federal Reserve to the slaying of journalist Jamal Khashoggi, a contributor to the Post, inside the Saudi consulate in Istanbul. The transcript of the interview does not necessarily substantiate Trump’s complaint. True, the story that Dawsey and Rucker wrote emphasized the edgy angles—Trump slams fed chair, questions climate change...read the headline—and the reporters noted, perhaps gratuitously, that their conversation with the president had been “discordant.”

But Trump really did say what the two journalists reported. Asked if he feared the prospect of recession, the president said that he was making deals with China and Europe “and I’m not being accommodated by the Fed,” a reference to the fact that the Fed continued to raise interest rates, rocking the stock market. “I’m not happy with the Fed. They’re making a mistake because I have a gut, and my gut tells me more sometimes than anybody else’s brain can ever tell me...So far, I’m not even a little bit happy with my selection of Jay [Powell, the Fed chairman]. Not even a little bit.”

A professional politician would not have answered so bluntly. On the subject of the Fed, for example, he might have said, “Some people have noticed that in the entire tenure of my predecessor, the Fed raised the rate twice, where this Fed has raised it seven times in my two years as president. Of course, that might be in response to our very strong economic growth.’’

On the other hand, there can be little doubt that, had the subject of the Fed come up over a Trump family dinner, he would not have answered the question any differently than he did for the Post. That points to one of the ironies of the enmity between this president and his press corps. For all of the distaste for Trump’s communications style, he is more accessible and his thinking more transparent than any other president in memory.

Trump understands his own marquee value and believes deeply in it. He seems less accepting of the fact that the Trump media allure is indifferent to context: Trump’s draw abides equally in friendly and unfriendly settings. He seems particularly galled by the souring of his relationship with Joe Scarborough and Mika Brzezinski, hosts of MSNBC’s Morning Joe, whom he once considered as sort of friendly colleagues. Trump blames the rupture on a business decision by NBC to cater to never-Trump viewers. “The funny thing is, it’s NBC, and I made NBC a fortune on The Apprentice,” he said. “When they were down on the bottom and I had, in many cases, the number-one show in television during many evenings, but also it was the only show in the top ten for a long time. I was very good to NBC. And it amazes me that Steve Burke”—CEO of NBCUniversal—“and these people at NBC would have allowed that to happen, this hatred.”

While the Trump–Morning Joe discord may be dismissible as a celebrity spat, the tensions between the president and the White House press corps exist on a far more meaningful plane. Trump himself seemed to understand this when he nixed a plan by senior aides to move the press corps outside the White House. (“They are the opposition party,” one proponent explained at the time.) Trump likes having reporters close, but he still hasn’t quite settled on an approach to dealing with them. For a long stretch early in his tenure, he avoided press conferences and most other direct sessions with reporters. “I tried that,” he told me. “That didn’t work too well.” Concerned that the void was being filled by stories suggesting that he wasn’t up to the job, Trump adopted his current approach: more press conferences, of both the formal and informal varieties, and even inviting reporters to Oval Office meetings. “The good thing about doing a lot is, the one thing they don’t say is ‘He’s incompetent,’ ” Trump said. “Now they don’t say that anymore.”

Regarding that staple of political journalism, the White House press briefing, Trump has gone in the other direction. Once a daily fixture (and a source of reliably good entertainment), the briefings have been reduced to a trickle, with only five conducted by Press Secretary Sarah Sanders from last August to the end of the year, at Trump’s instruction. “I look at a lot of these people, and the hatred in their eyes as they’re asking Sarah—who’s a wonderful person, I mean, she’s before me now [i.e., in the room], but I would tell you if she wasn’t, Sarah’s a wonderful person—and for her to be treated like that, with the hatred of the question...” Trump said. “I’m not just mentioning Jim Acosta”—the CNN correspondent who turned the briefings into performance art—“you have some, I think, that are worse than him. The hatred when they ask a question is just incredible.

“I know reporters that would love to be nice to me, love to be. I really think they like me and they like what I stand for,” Trump continued. “And then you see them and they’ve got a negative bent. And I really strongly believe that their bosses tell them that they must do that...It’s not only a political view, it’s also a business view. It’s their business model.”

That suggests a misunderstanding on Trump’s part about how journalists work. No reporter needs instructions from the boss to aggressively pursue the big scoop that may prove to be Trump’s Watergate.

But Trump is right in thinking that Trump- centric coverage has become a nice little business model for news organizations from Fox News to CNN to The Washington Post. After Trump began referring to “the failing New York Times,” Dean Baquet, taking the bait, publicly declared that his paper’s aggressive coverage of the president had been very good for business. But before Trump came along, the Times had indeed been failing, or at least flailing—the impact of its journalism dulled by the Internet, its advertising revenues drained by competition from such entities as Facebook and Google. The paper’s survival, much less its long-term health, was anything but certain.

As Jill Abramson notes in her book, the paper’s discernible tilt away from its formerly fussy insistence on impartiality paid off. “Given its mostly liberal audience,” she wrote, “there was an implicit financial reward for the Times in running lots of Trump stories, almost all of them negative: They drove big traffic numbers.” According to Abramson, the Times racked up six hundred thousand new digital subscriptions in the fiscal quarters around Trump’s election, a roughly 40 percent increase. The company’s stock price had hit a three-year low of $10.80 on November 3, 2016, five days before the election; last November 1, the shares reached a twelve-year high of $28.23. Abramson quotes the former Times reporter Jeff Gerth, who referred to the paper and Trump as “sparring partners with benefits.”

Back in the early months of the Trump presidency, I had asked Liz Spayd, the public editor, if the Times’s new business model was to become a sort of high-end Huffington Post.

“I hope that is not the case,” she said. “I think that would be a sad place for this country to find itself, that one of the strongest and most powerful and well-financed newsrooms in the country would speak and have an audience only on one side of the political aisle. It’s very, very dangerous, I think.” Spayd had become the voice of the old traditions at the Times, a position that earned her the opprobrium of progressive critics outside the paper (“This editor appears to be from 1987 or earlier,” Keith Olbermann tweeted. “Sorry—get in the game or get out”) as well as inside the newsroom. Five months into the Trump presidency, her job was eliminated; she now consults for Facebook. Another example of this cost-benefit approach was the wholesale dismissal of the paper’s copy editors, whose role had included safeguarding the old standards within the news sections. (Dean Baquet declined to be interviewed for this article.)

One problem is that there will come a day relatively soon, whether it’s next week or next month or in the middle of the next decade, when Donald J. Trump will no longer be president. Whoever is running the Times when that day arrives will have to somehow refit the Trump model to whatever personality and news environment comes next. By then, the Times’s core identity as the authoritative paper of record may be difficult to reclaim.

Toward the end of her book, Abramson mentions the epitaph above the grave of the Times editor Abe Rosenthal, who helped shepherd the paper through some of the biggest social and political tumults of the last half of the last century, including Vietnam, Watergate, and the rise of Reagan conservatism. Rosenthal’s grave marker reads: “He kept the paper straight.”

Those words will not likely be affixed to those who directed the paper through the challenging tenure of the forty-fifth president. More fitting final words for them might well be: “Trump made us do it.”

Peter J. Boyer spent 18 years as a staff writer at The New Yorker, where he wrote on a wide range of subjects, including politics, the military, religion, and sports. Before joining The New Yorker in 1992, Boyer was a national correspondent for the Los Angeles Times, the media reporter for the New York Times, a contributing editor at Vanity Fair, and a television critic for National Public Radio’s “Morning Edition.” As a correspondent on the PBS documentary series, “Frontline,” he won a George Foster Peabody Award and an Emmy for his reporting, as well as consecutive Writers Guild Awards for script writing. Boyer’s New Yorker articles have been included in the anthologies Best American Political Writing, Best American Spiritual Writing and Best American Crime Writing, as well as Best American Science Writing.