The (Almost) Lost Speech of Justice Anthony Kennedy

How his insightful remarks about the Constitution inadvertently make the case for a Supreme Court "media pool"

As a matter of policy, at least as far as I know, the out-of-court public words of the justices of the United States Supreme Court are not automatically transcribed and recorded the way the public words of our presidents are.

There is, unfortunately, no "Supreme Court media pool" that follows the justices around the nation and the world the way there is a White House "media pool" that tracks the president's every public move and utterance. A president can die or "make news" at any moment. So can a justice. But there is only one of the former and nine of the latter. You do the math.

The curious result of this indifferent treatment -- and, let me be clear, the media are largely to blame for this as well -- is that the justices move between two very different worlds. When they are in session in Washington, they operate in near total secrecy, emerging only to hear argument and release their opinions. And when they are not in session, they operate free from many of the chronicling obligations that shape the lives of other public officials. They speak in public often, and often say fascinating things, but they often impose in these appearances onerous restrictions upon their way their words can be reported.

Several of the justices, for example, do not permit audio or video broadcasts of their speeches, lectures or public appearances. Last year, Justice Antonin Scalia spoke at the University of Wyoming at an event where photo identification was required and no cell phones or cameras were permitted at the venue. It is ironic, indeed, that an institution whose justices profess to be so concerned about being quoted out of context -- the primary reason the justices often give for their refusal to allow cameras in their courtroom -- make it more difficult for journalists to quote them in context by often precluding an official "record" of what was said.

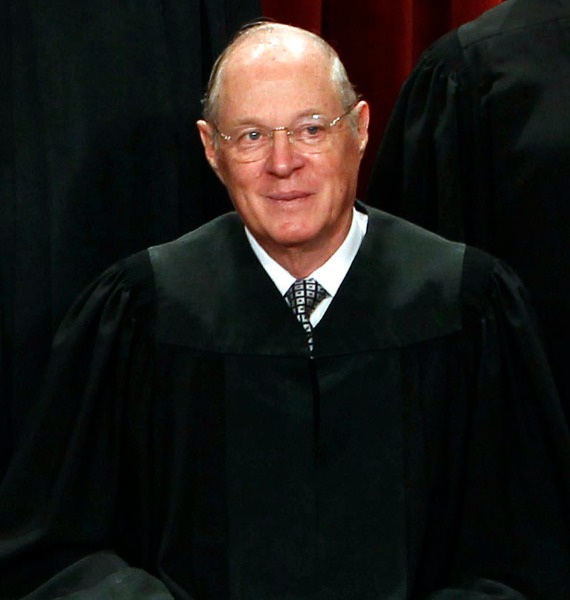

All of this is a preface, background really, to a story about Justice Anthony Kennedy. Last Monday, before an audience at the Chautauqua Institution at the very western tip of the state of New York, Justice Kennedy, the single most important justice on our deeply divided high court, delivered an insightful speech about his perceptions of freedom and democracy. I did not know in advance about his appearance, although it was publicized, and I did not attend and cover the event, even though it was open to the media. In this I was not alone -- there was barely any coverage of the justice's remarks.

What little I saw reported about what Justice Kennedy said that night -- in a piece written by an earnest college student -- raised as many questions as it answered but intrigued me enough to make me want to know more. So I contacted the good folks at the Institution to see whether anyone had recorded or transcribed the speech. "Unfortunately, audio or video recordings of any kind were not allowed during Justice Kennedy's lecture," I was told, before I was referred to the Supreme Court.

I then queried Court staff: There's surely more to what the justice said than appears in this story, I said. The justice seems to be contradicting himself and that doesn't make sense to me so can't the Court find me a copy of his speech so I can ensure that I am citing him in full and in context? There was some back-and-forth and then the Court did something it deserves a great deal of credit for. It gave me an opportunity to hear an audio recording of Justice Kennedy's speech -- made for archival purposes by the Institution-- after I promised I would not broadcast it.

Last night, I listened to the speech and to the question-and-answer session that followed it. I wish you could hear it for yourself. Not because Justice Kennedy said anything shocking but because he was so earnest and eloquent in sharing his views about the history of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights. In an age where judges often lament the public's dwindling knowledge about basic civics, Justice Kennedy lectured to his audience like a friendly college professor. There can be no doubt that the crowd learned from him-- and that you would have, too.

The Speech

He spoke for approximately 40 minutes. But it was about two-thirds of the way in, when he began to discuss the first amendment, that he said something, and said it in a way, that I found particularly interesting. By means of a "law school" hypothetical, the justice asked his audience to pretend first that "you are a government official, bound by the Constitution... You'll be a judge, a federal judge." Next, he told the audience, "assume this... you may not like it... but assume that you as a personal matter strongly reject:

the idea of ethical relativism, moral relativism. That's the philosophical school which says (and here the justice's voice elevated a few octaves and turned sing-song-y, as though he were trying to mimic a new-age guru) that all ideas are of equal value, you have a right to think what you want, all books are the same, all music is the same... the philosophy that one person cannot insist on the correctness of his or her views; the philosophy that there are no absolutes in art, architecture, literature, aesthetics, beauty, religion, the fact that you can and must tell your kids what's a good book and not a bad book.

"Now how can you be a judge and enforce the first amendment," Justice Kennedy asked, "If this is your personal philosophy?" He then said:

The first amendment says all rights are protected. All movies are protected. All music is protected. Aren't you a hypocrite? And if as a judge you are enforcing some mandate that is contrary to your conscience and your ethics maybe you should resign. How can you do this? There's an answer. The Constitution controls only the government. The first amendment says it's not for the government to say that this book is good and this book is bad, it's not for the government to say that this movie is good and this movie is bad. It's doesn't follow that the public cannot say so....

And here the hypothetical seemed to end. And here Justice Kennedy seemed to be making his own point: "A nation that's in the grips of moral relativism, as a private philosophic matter, cannot protect basic values," he said, before offering an example about a group of students he met last summer who later went to Europe and then returned to "give little reports on what they had done." As the justice recounted, a young woman said to him: "'And I elected to go to Auschwitz and it was very important.'

"'Why was it important?' Justice Kennedy said he asked the student. And she said: "That's where Schindler's List was filmed.': Justice Kennedy then said:

Well, I had this sinking feeling that even with the crime of the enormity of the Holocaust, or of the Stalin massacres, that we are reluctant to condemn.... A strong society, a happy society, a society with a civic consensus, must make judgments on what's good, bad, beautiful, ugly, right, wrong. That's not just your right as a citizen. In my submission it's your responsibility.

(An aside: If I were there that night, and I got to ask a follow up, I would ask the justice to explain why he thinks Americans "are reluctant to condemn" when there is so much evidence around of us daily condemnations of just about every facet of life. Condemnations on television, on radio, on the Internet, in newspapers, at political rallies, in music. Who exactly, I would ask the justice, is not making judgments on "what's good, bad, beautiful, ugly, right, wrong"?)

Next came the question-and-answer session. Indented below are Justice Kennedy's words from some of the responses to some of the questions asked of him:

On Public Discourse

I think we have to master the art of gentle persuasion. I think that the concept is that it mature and that the civic discourse that underwrites it also matures. And I see in this nation a discourse that's hostile, fractious, uncompromising... look at some of our television programs-- Hardball! Crossfire! That's not the mark of a society that's rational and probing and thoughtful...

On New Technologies

It's interesting that the more technologically advanced we become the more vulnerable our freedoms are. I just don't know quite what to do about that. The Internet is changing the world... But I am concerned that the Internet changes the way we think about thought. We think about thought as being just factual factoid information... But that's not thought. That's not reflection.

On judicial independence

We have to be pretty careful [about giving state judges lifetime appointments]... Judges have a tremendous amount of power? Should they be completely immune from political control? It is the obligation of the bar, and of the citizens, and of the press, when there is a good judge under attack (and here the justice's voiced raised) to defend that judge. Their that's obligation to do and they don't do it...

On the need for the police court beat:

I am very concerned that with the financial difficulties newspapers have now that we have no trained reporters in police courts. It takes a trained reporter to know when that police court judge is properly angry with an attorney who is doing the wrong thing or if the judge is just cranky and temperamental and biased. And we are losing that ability to keep track...

On Cameras in the Supreme Court

The whole part, the whole point, the whole function, the whole duty of the Supreme Court is to teach. To give reasons for what we do. You could learn a lot. On the other hand we teach by keeping the press out. We teach that we are judged by what we write. We don't go around giving press conferences "how great my decision was" or "how bad the dissent was." We are judged by what we write.

From an institutional standpoint know that my colleagues and I are not immune from the instinct to grab a headline and I don't want to think that my colleague asked a question for the benefit of the press. I don't want to introduce that insidious dynamic between myself and my colleagues.

Postscript

Following this episode, I am now more convinced than ever that there ought to be a Supreme Court media pool. The public remarks of every justice at every appearance should be covered in full. And organizations of learning or higher education ought to require the assent of any visiting justice to the creation (as the very least) of a public transcript of his or her remarks. Would that chill the candor of the justices as they go around the country speaking and teaching? Perhaps. But then the justices wouldn't be at all true to Justice Kennedy's creed that "the whole duty of the Supreme Court is to teach."

As an institution, the Supreme Court needs to better explain itself, and the law, and the justice system, to its constituents. No one can teach basic constitutional principles than the justices. No one can help educate the American people about the glory of the law better than the highest judges in the land. Transcribing and recording their public remarks to ensure that there is a complete record, making it easier for reporters to get accurate quotes in context, is the easiest, safest way for them to do so. Every speech. Every justice. The American people deserve it.